Understanding Chinese characters

Learning Chinese characters can be a struggle to begin with but once the basics have been mastered each new character can take you on a fascinating journey through Chinese history and culture. In the language section we have an introduction to the Chinese language and also show how the characters are drawn with brush or pen strokes. Here we look at the basic classes of characters and the origins of some of the most frequently used characters in Chinese.

Ancient scripts

The Chinese script is not the oldest known script. The Cuneiform script from about 5,500 years ago was used in Mesopotamia (present day Iraq and Iran) and was in use for about 3,000 years. Over 750,000 clay tablets using the cuneiform characters have been unearthed. The language was decoded in 1850 by Sir Henry Rawlinson ➚. In Egypt at around 5,000 years ago the famous hieroglyphic script developed; in this case the characters are pictograms but the script fell out of use by 500CE. In India the short-lived Harappa Culture (4,500-3,700BCE) also had an ancient script. The written script in China can only be traced back with certainty to the oracle bones of about 1,200BCE. However the script had a considerable vocabulary and signs of simplification at that date which strongly suggest the origin of the script goes back much further. It is likely that earlier writings were made on perishable material such as bamboo that have now all been lost. What makes Chinese unique is that the script forms have evolved directly to become the present day characters and so it is the longest lived script still in use in the world. As well as the oracle bone script, inscriptions became common on bronze ware from the Shang and Zhou dynasties. These inscriptions used the 金文 Jīn wén script which is less informative than the oracle bones as it just records who owned and made the vessel - the longest inscription is just 42 characters long. Around 2,000 of these Jinwen characters are ancestors of modern day forms.

Chinese Character categories

The characters are split into groups. The first are the ancient pictographs, these characters are derived from drawings of objects in everyday life probably over 10,000 years ago. During the period 5,000 to 6,000 years ago the pictures were augmented with indirect and abstract symbols, this class is called the 指事 zhǐ shì ‘refer to things’.

Different kingdoms in the China area devised their own characters and it all became quite confusing. It was the discovery of writing on oracle bones from the late Shang dynasty (c. 1200BCE) that has greatly added to the knowledge of the characters used in ancient days. At this time the characters remained mainly pictorial, it was then and in the later Han Dynasty that characters began to include components that indicate how they should be pronounced - the phonetic part. Up until then looking at a character gave no hint as to how to say it. Nowadays about 80% of characters have a phonetic part indicating how it might be pronounced, these are called the 形声 xíng shēng ‘appear sound’ class of character. Over the centuries the spoken language has changed and so knowing the phonetic part is not a totally reliable guide to pronunciation. As well as phonetic components there are a relatively small number of ‘meaning’ or ‘determinative’ components; these radicals indicate that the character which uses it is in a particular class of thing - for example the 木 wood radical is used in over 1,500 characters all with an association with plants or wood and 心 heart radical is used in many characters indicating an emotion.

Since the Han dynasty (over 2,000 years ago) the core characters have remained pretty much unaltered but new characters are always needed and archaic ones have fallen out of use. The classic script which came into use c. 400CE has been used for official documents ever since. The writing of officials and scholars was not used by everyday people and the term ‘Chinese Latin’ has been used to make the allusion to Europe when only the educated elite would use Latin not the vernacular language.

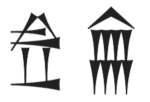

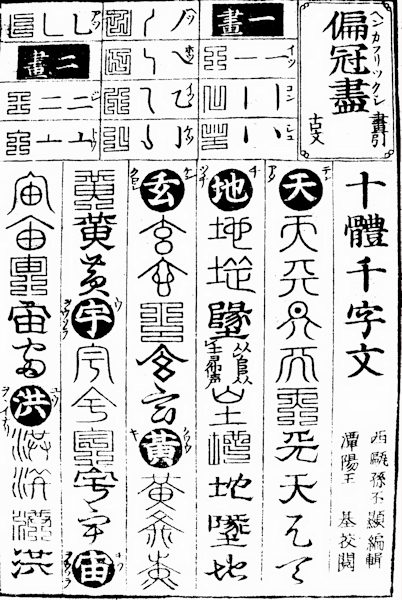

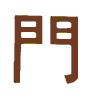

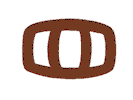

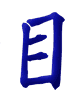

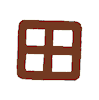

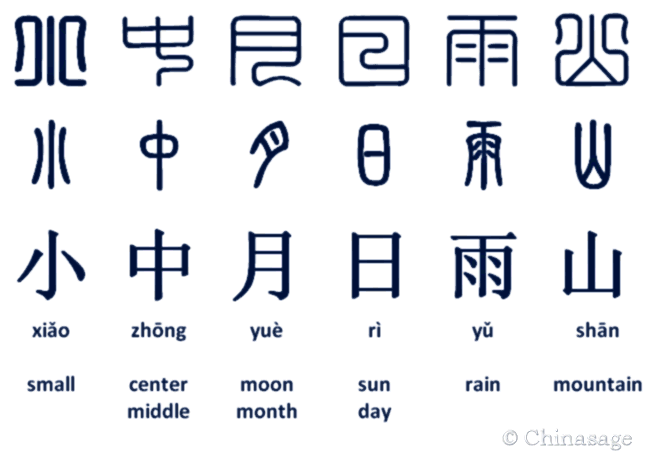

Over the centuries the original pictures have been simplified for ease of writing with a brush. In the list of characters below on the left in brown is the original script ‘picture’ from the Shang or Zhou dynasties - 3,000 years ago. In blue is the modern script which uses lines and avoids curves as much as it can. These simplifications can make deciphering characters difficult.

The story of how characters originated

One well known story is that the legendary god/emperor Fuxi devised the characters from the Eight Trigrams from Yin/Yang system and that the characters developed from these eight. There is neither logic nor evidence for this idea.

According to another tradition it was Cang Jie ➚ 仓颉 who devised the characters at the time of the Yellow Emperor. He observed the footprints of animals and birds and realized how just the shape of the print uniquely identified the animal. He could just draw the simple footprint shape rather than the whole animal. He then applied this same principle to devising pictographs for everyday objects (sun, moon, earth, clouds, birds, animals and so on). These characters (象形 xiàng xíng image shapes) have made their way into Japanese (Kanji ➚) and Korean scripts (Hangul ➚) too; so learning Chinese characters helps you read a little in Japan and Korea.

There is now a mind boggling set of 200,000 or so characters but fortunately, to get by in Chinese, you only need to master about 500 of them. The vast majority (90%) are made up of a ‘radical’ combined with another element rather than a single pictorial representation. Liu Xin ➚ and Xu Shen ➚ of the Han Dynasty used six classes of character: pictographs; indirect symbols; associative compounds; mutually interpreted symbols; borrowed characters and determinative phonetics. Xu Shen produced the influential 说文解字 Shuō wén jiě zì ➚ in about 100CE where he identified 540 common components (mainly radicals).

Character forms

The form of the characters evolved from the early oracle bones. The 小篆 Xiǎo zhuàn ‘small seal’ script has curves and fine lines and was the standard form imposed by the Qin dynasty. The forms are still used today on seals and other pieces of artwork. These replaced the early 大篆 Dà zhuàn ‘large seal’ form that was used in the Zhou dynasty principally on bronze work. The change in form was driven by using a brush rather than a stylus to inscribe them. In the latter part of the Zhou dynasty an unusual script became popular, this was the ‘Bird and insect script ➚’ where characters were drawn as stylized birds and insects, it fizzled out when the Qin dynasty came to power.

It was during the following Han dynasty that the characters took the step of being square in form with straight strokes and not curves. The 隶书 Lì shū ‘clerical script’ and 楷书 kǎi shū ‘standard script’ had evolved during the Qin dynasty because they were faster to write with a brush than the older ‘seal’ forms. The regular ‘kaishu’ script has less variation of stroke than ‘lishu’; Lishu is more suited to calligraphy. Writing individual strokes in this script with a brush is slow, and so for reason of speed and also artistry a different script is used. The common form of this running or cursive script is 草书 cǎo shū ‘grass script’ but this can be challenging to read.

By the Song dynasty the printing of books became common. In a break to using a brush, the characters were engraved on wood with a knife. This made straight strokes easier to make compared to curves. It uses thin horizontal but thick vertical strokes. This 宋体字 Sòng tǐ zì style of calligraphy is still commonly seen in books and fine art.

Picture characters

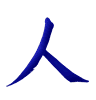

The character for a person is a much simplified pictogram of a figure leaning to the left, the leftmost stroke originally represented the arm. Now it is only a pair of legs.

The character for a person is a much simplified pictogram of a figure leaning to the left, the leftmost stroke originally represented the arm. Now it is only a pair of legs.

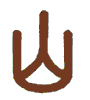

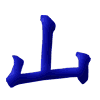

One of the clearest pictographs represents mountain. The original pictograph had two smaller humps with a central mountain, these have been simplified to become vertical strokes over the years. This character is used in the names of two provinces Shanxi 山西 (mountains west) and Shandong 山东 (mountains east).

One of the clearest pictographs represents mountain. The original pictograph had two smaller humps with a central mountain, these have been simplified to become vertical strokes over the years. This character is used in the names of two provinces Shanxi 山西 (mountains west) and Shandong 山东 (mountains east).

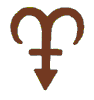

A sheep or goat is recognizable from its horns. The modern character for a sheep has two dot strokes for the horns, a stroke for the eyes and one for the mouth.

A sheep or goat is recognizable from its horns. The modern character for a sheep has two dot strokes for the horns, a stroke for the eyes and one for the mouth.

The pictogram for a bird has it sitting on a perch with one eye represented by a dot. This is one of the more pleasing simplifications as it manages to retain the original essence of the subject with very few strokes.

The pictogram for a bird has it sitting on a perch with one eye represented by a dot. This is one of the more pleasing simplifications as it manages to retain the original essence of the subject with very few strokes.

The pictogram for a fish shows a head and a scaly body completed with a line to represent the fins. A fish is used as a symbol wishing good luck as it sounds the same as the character 余 yú for abundance and affluence.

The pictogram for a fish shows a head and a scaly body completed with a line to represent the fins. A fish is used as a symbol wishing good luck as it sounds the same as the character 余 yú for abundance and affluence.

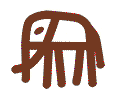

In the modern character for an elephant the head is shown with the tusk and trunk protruding, so there are seven strokes in all to form the body. The elephant's head is drawn as an oblong. Several animals are captured as an easy to see pictogram in the same way including: horses, dogs and rabbits. Asian elephants used to be widespread in China, today they are only seen in Yunnan province. A piece in Chinese chess is called an elephant, and the game itself is called Xiangqi or elephant game.

In the modern character for an elephant the head is shown with the tusk and trunk protruding, so there are seven strokes in all to form the body. The elephant's head is drawn as an oblong. Several animals are captured as an easy to see pictogram in the same way including: horses, dogs and rabbits. Asian elephants used to be widespread in China, today they are only seen in Yunnan province. A piece in Chinese chess is called an elephant, and the game itself is called Xiangqi or elephant game.

The character for a vehicle used to make sense in its old script form, 車 as it was a cart seen from above with an axle on either side. In the last major simplification of the Chinese script brought in by the People's Republic the character has been simplified to the extent that the ‘cart’ form is hard to make out.

The character for a vehicle used to make sense in its old script form, 車 as it was a cart seen from above with an axle on either side. In the last major simplification of the Chinese script brought in by the People's Republic the character has been simplified to the extent that the ‘cart’ form is hard to make out.

Of fundamental interest to our ancestors was the passage of the seasons, and the moon determined the date (from which we get the word month). The Chinese character for moon is an idealized crescent moon.

Of fundamental interest to our ancestors was the passage of the seasons, and the moon determined the date (from which we get the word month). The Chinese character for moon is an idealized crescent moon.

The character for sun is simply a picture of a radiating circle. The ‘square’ form of all characters in this script forces the shape to be a box rather than a circle. In many cultures the sun is shown with an all seeing eye at its center, so the pictogram has a dot in the middle.

The character for sun is simply a picture of a radiating circle. The ‘square’ form of all characters in this script forces the shape to be a box rather than a circle. In many cultures the sun is shown with an all seeing eye at its center, so the pictogram has a dot in the middle.

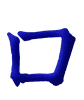

Another round pictogram is mouth which has become a plain square without any embellishment. As a radical component it is often used in characters relating to speech.

Another round pictogram is mouth which has become a plain square without any embellishment. As a radical component it is often used in characters relating to speech.

A straightforward character to memorize is a gateway or entrance as it is just a doorway with two doors. As with ‘vehicle’ the traditional form 門 has recently been simplified for quicker drawing but retains the basic shape of how you would draw a gateway.

A straightforward character to memorize is a gateway or entrance as it is just a doorway with two doors. As with ‘vehicle’ the traditional form 門 has recently been simplified for quicker drawing but retains the basic shape of how you would draw a gateway.

The pictogram for an eye, is an eye on its side. The central iris of the eye has been reduced to two short strokes in the middle.

The pictogram for an eye, is an eye on its side. The central iris of the eye has been reduced to two short strokes in the middle.

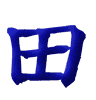

A field is an ancient character. It is an area divided up for cultivation with cross-paths.

A field is an ancient character. It is an area divided up for cultivation with cross-paths.

A word of universal importance, particularly ages ago when almost everybody worked the land, is the one for rain. It has little drops falling downwards from the sky.

A word of universal importance, particularly ages ago when almost everybody worked the land, is the one for rain. It has little drops falling downwards from the sky.

Another pictogram that once it is visualized as a picture works well is heart. It has a simple shape, the dot (dian) strokes give an impression of blood in motion. You will see heart in combination with many other characters denoting a strong emotion, for example 热心 rè xīn is literally hot heart meaning passionate, enthusiastic.

Another pictogram that once it is visualized as a picture works well is heart. It has a simple shape, the dot (dian) strokes give an impression of blood in motion. You will see heart in combination with many other characters denoting a strong emotion, for example 热心 rè xīn is literally hot heart meaning passionate, enthusiastic.

Abstract notions

Characters have to identify more than just physical objects, words are needed for more abstract notions like spatial relationships. The following is a selection of a few common characters where the drawing brings an abstract idea to life.

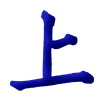

To give the concept of up; above; or over what could be simpler than an upright character? It is used in the name for Shanghai (上海) to roughly mean on-sea.

To give the concept of up; above; or over what could be simpler than an upright character? It is used in the name for Shanghai (上海) to roughly mean on-sea.

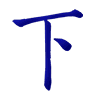

Once you have chosen how to represent up as a character then down; below or descend must be the mirror image of it.

Once you have chosen how to represent up as a character then down; below or descend must be the mirror image of it.

Another abstract notion is middle or center and this is quickly brought to mind by a symmetric figure, originally representing an arrow hitting the center of a target or may be the central portion of a flag. Most significant is its use in the Chinese word for China itself: 中国 zhōng guómiddle or center country.

Another abstract notion is middle or center and this is quickly brought to mind by a symmetric figure, originally representing an arrow hitting the center of a target or may be the central portion of a flag. Most significant is its use in the Chinese word for China itself: 中国 zhōng guómiddle or center country.

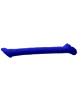

The easiest of all the abstract words are the numbers: 1, 2 and 3. They follow the Arabic/Indian system of being based on a count of strokes. So 1 is just one stroke.

The easiest of all the abstract words are the numbers: 1, 2 and 3. They follow the Arabic/Indian system of being based on a count of strokes. So 1 is just one stroke. Two: 2 must be two strokes.

Two: 2 must be two strokes. Three: 3 follows the pattern with three strokes. You can think of Arabic 3 as three horizontal strokes linked together. Thereafter as in the Arabic system Chinese does not continue to add more strokes for 4; 5 etc..

See numbers section for the full set.

Three: 3 follows the pattern with three strokes. You can think of Arabic 3 as three horizontal strokes linked together. Thereafter as in the Arabic system Chinese does not continue to add more strokes for 4; 5 etc..

See numbers section for the full set. Another abstract notion is open space or vastness. The character consists of mainly open space, it used to have a character inside 廣. This character may be familiar to you already as it is part of the name of the ‘vast’ provinces Guangxi: 广西 vast west and Guangdong: 广东 vast east.

Another abstract notion is open space or vastness. The character consists of mainly open space, it used to have a character inside 廣. This character may be familiar to you already as it is part of the name of the ‘vast’ provinces Guangxi: 广西 vast west and Guangdong: 广东 vast east.

When you have relative abstract terms like up and down; you also need big and small. Big is just a big person 人 ren with an extra stroke suggesting out-stretched arms.

When you have relative abstract terms like up and down; you also need big and small. Big is just a big person 人 ren with an extra stroke suggesting out-stretched arms.

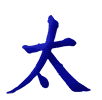

If you want to emphasize size even more so that it becomes excessively large, then just adding an extra stroke to big 大 da makes it too or excessive. The extra stroke was originally a line for emphasis but this has become a dot.

If you want to emphasize size even more so that it becomes excessively large, then just adding an extra stroke to big 大 da makes it too or excessive. The extra stroke was originally a line for emphasis but this has become a dot.

Another adaption of the big character is to add another heng line stroke at the top. This gives the concept of heaven or sky - a very large space that is above men. The top stroke represented a large head to emphasize idea of 'top'.

This is the second tian we have used in this section. Tian heaven and Tian field are distinguished by tones in pinyin. Heaven is first tone tiān while field is second tone tián.

Another adaption of the big character is to add another heng line stroke at the top. This gives the concept of heaven or sky - a very large space that is above men. The top stroke represented a large head to emphasize idea of 'top'.

This is the second tian we have used in this section. Tian heaven and Tian field are distinguished by tones in pinyin. Heaven is first tone tiān while field is second tone tián.

The opposite to big is small and it is represented by an already small thing chopped in two.

The opposite to big is small and it is represented by an already small thing chopped in two.

Cutting up something already small makes it even less. So another ‘cut’ stroke turns small (xiao) into less (shao).

Cutting up something already small makes it even less. So another ‘cut’ stroke turns small (xiao) into less (shao).

Character combinations

Once you have a basic set of characters they can now be combined into composite characters in various ways. This class of characters is called the 会意 huì yì associative compounds. The way they are combined can become complicated as sometimes the original meaning has been lost and the combination of characters has no discernible logic.

If you combine moon and sun you have the two brightest objects in the sky. So the combined character of sun 日 and moon 月 makes the character for bright 明.

If you combine moon and sun you have the two brightest objects in the sky. So the combined character of sun 日 and moon 月 makes the character for bright 明.

Combining the character for rain 雨 with a broom gives another clear meaning - rain you need to brush away which is snow 雪.

Combining the character for rain 雨 with a broom gives another clear meaning - rain you need to brush away which is snow 雪.

Other characters are formed by combination with rain 雨. In this case field 田 and rain together make thunder 雷. This gives the evocative link of hearing an approaching storm out in the fields.

Other characters are formed by combination with rain 雨. In this case field 田 and rain together make thunder 雷. This gives the evocative link of hearing an approaching storm out in the fields.

The field 田 character can be combined with other characters. If it is added to strength li 力, itself a pictograph of a muscled arm, then the character for male is constructed, reflecting the traditional role of men as the muscled toilers out in the fields.

The field 田 character can be combined with other characters. If it is added to strength li 力, itself a pictograph of a muscled arm, then the character for male is constructed, reflecting the traditional role of men as the muscled toilers out in the fields.

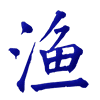

The fish 鱼 character produces a number of related fishy meanings. If the radical for water shui 水 is added to it as three ‘drops’ then we get the action of fishing. This is also a ‘phonetic’ clue as fish and fishing are both pronounced the same way.

The fish 鱼 character produces a number of related fishy meanings. If the radical for water shui 水 is added to it as three ‘drops’ then we get the action of fishing. This is also a ‘phonetic’ clue as fish and fishing are both pronounced the same way. A quality of both fish and meat is that they must be eaten when fresh as they go off quickly. So to convey the notion of freshness the characters for fish yu 鱼 and sheep yang 羊 are combined together.

A quality of both fish and meat is that they must be eaten when fresh as they go off quickly. So to convey the notion of freshness the characters for fish yu 鱼 and sheep yang 羊 are combined together.

Finally as an example of a more obscure but somehow delightful origin is the character for ancient. It is a combination of ten shi 十 and mouth kou 口 perhaps indicating words passed between ten people, or passed down through ten generations making it very ancient indeed.

Finally as an example of a more obscure but somehow delightful origin is the character for ancient. It is a combination of ten shi 十 and mouth kou 口 perhaps indicating words passed between ten people, or passed down through ten generations making it very ancient indeed.

A set of ancient pictographs showing the different representations in ‘large seal’ 大篆 Dà zhuàn (over 2,000 years old) ; 小篆 Xiǎo zhuàn ‘small seal’ (about 2,000 years old) and modern script. The first set are the picture based representations for bird, fish, sheep or goat, man, large and heaven. There is quite a lot of variation between ancient forms as it was never standardized.

The second set of ancient pictographs shows the different representations in ‘large seal’ 大篆 Dà zhuàn (over 2,000 years old) ; 小篆 Xiǎo zhuàn ‘small seal’ (about 2,000 years old) and modern script. The second set are the picture based representations for small, middle, moon, sun, rain and mountain.

Phonetic Characters

Devising individual ‘pictures’ beyond a few hundred characters becomes unmanageable. Quite apart from the difficulty of making a recognizable representation, there is the problem of giving a guide on how to pronounce the character as a picture gives no clue. To get around this issue most Chinese characters use a radical that gives a hint to the pronunciation rather than the meaning. An example is the character for horse 马 mǎ. The phonetic sound ‘ma’ can be found in other characters pronounced ‘ma’ such as mother 妈 mā and question mark 吗 mǎ.

Unfortunately over the years pronunciation in Chinese (as with all other languages) has changed and the phonetic part has become in some cases misleading. For example the character for wrap; cover 包 bāo does give the pronunciation for 饱 bǎo but for 炮 pào the ‘b’ sound has become a ‘p’. The phonetic characters represent about 80% of all characters.

Phonetic Borrowing

In a further twist of complexity there are characters that have ‘robbed’ other characters of their representations. When two characters were pronounced the same then they were often written down using the most common character that sounded the same - almost like a phonetic spelling. Over time a character was robbed of its old form and to make this unambiguous the old usage had a component added to distinguish the two meanings. As an example 莫 mò ‘do not’ has taken over the representation for sunset (a representation of the sun seen through trees). The character it robs from is now written as 暮 mù which still means ‘sunset; dusk’. They used to be both pronounced the same: mù. To distinguish them the character 日 rì ‘sun’ was added beneath 莫. Looking at 莫 mò nowadays gives no clue as to why ‘do not’ has this pictographic representation.

Chinese Words

There is only so far you can go with characters, they all need to be easy to recognize uniquely and have to be learned by heart. Basic literacy is considered to require learning 2,000 characters. This figure clearly indicates that characters are not ‘words’, there are hundreds of thousands of words in both English and Chinese. In Chinese a single character rarely establishes meaning, this is certainly true in spoken Chinese when hundreds of characters sound exactly the same. To give a clear meaning two or more characters are used together to form a word. Typically the characters reinforce each other in meaning, both separately refer to more or less the same thing and so dispel ambiguity. A classic example is 朋友 péng yǒu where both 朋 and 友 independently mean friend but taken together they unambiguously mean friend. In my modest dictionary there are 15 homophones for 朋 péng including 膨 swollen; 棚 shed; 鬅 disheveled and 篷 sail; while 友 yǒu has 13 homophones including: 懮 relaxed; 牖 lattice window; 黝 dark green and 泑 ceramic glaze. Hearing péng yǒu with these two characters combined immediately identifies the meaning as friend.

Putting characters together forms a composite ‘word’ idea. 笑话 xiào huà joke is made up of 笑 xiào laugh; smile and 话 huà speech; words. There are many examples of this, where the combination conveys a more precise meaning than the individual parts.

It is also quite common for two characters together to have a meaning quite separate from the component characters, rather like the case of some components within a single character described above. For example 东 dōng 'east' and 西 xī 'west' in combination means literally east and west but also the vague thing, stuff 东西 dōng xī. Another example is 雪恨 xuě hèn avenge which is made up of 雪 snow and 恨 hate or 尘世 while chén shì mundane life is made up of 尘 dust, dirt and 世 age, era, life and finally 歪风 wāi fēng unhealthy trend, bad influence made up of 歪 crooked and 风 wind.

Vocabulary

We have some simple introductory lessons to basic Chinese where you can see the characters in use.

Sound files kindly provided by shtooka.net ➚ under a Creative Commons Attribution Share Alike License