The Needham Question

At the start of the nineteenth century China was the leading civilization on Earth and seemed set to continue in this role. China had the largest population, an advanced system of administration, the largest trade and the greatest wealth. Angus Maddison has estimated that China in 1820 represented one third of the whole world economy. China had used her great inventions of paper, printing, the compass and gunpowder to great effect. No nation could seriously rival China’s armed services or navy. And yet, somehow Europe quickly caught up and overtook China in only a hundred years. The question as to why China did not remain pre-eminent is called the ‘Needham question’.

Joseph Needham ➚ (1900-95) was the foremost scholar of China in the west. He had started his research work at Cambridge University, UK as a biochemist but after he became entranced by a young Chinese laboratory researcher his great intellect turned to China. It was at this time that Needham jotted down his famous question in 1942 ‘Science in general in China - Why did not develop?’ For the last fifty years of his long life he sought to create a systematic study of Chinese science and civilization to help to answer this question. After World War 2 he began working under a United Nation initiative in China; he had access to many books that had not been previously studied by Europeans. He met and conversed with many Chinese scholars about the development of science and technology.

Many have proposed answers to the Needham question and I summarize their analyses here. With China now poised to take center stage as the top nation there is a view that the period 1840-1980 should be considered as no more than a temporary blip rather than terminal decline. The question has wider implications than just China, as the same fate could befall us all in the future.

In the mid 15th century China seemed to believe it had all the science it needed - everything of use was adequately explained by the theories of five elements, yin-yang and the Yi Jing (I Ching). When the Jesuits arrived at Beijing in 1601, they saw an enlightened, prosperous country that they judged to be superior to Europe in almost every way. The only area where Europeans seemed to have the upper hand was mathematics and, derived from that, astronomy. When MacCartney visited China in 1793 with technological gadgets that failed to impress, the European perception was that little had changed in China at the macro level since Marco Polo’s visit in1275-92. So by 1920 Westerners were able to make the claim with some justification that China had ‘no science’ and it was true that China did not have the grounding in pure science that had been so crucial to western technological development.

Here are some of the suggestions that scholars have proposed to answer the Needham question:

1. Competing states

European scientific development took place when there were many states competing for supremacy and survival. Any engineering or scientific advance could give them the edge in conflict or trade. This is a form of Darwinism, as such competition drives rapid evolution. While Europe was in competitive turmoil China had no rivals and felt no need to reform. This is the strategy of many living things, when they have developed to securely occupy an environmental niche they may stay unaltered for millions of years. This theory is supported by China’s own early history. The Warring States period [476-221BCE], although disruptive and bloody, brought in many innovations and the development of guiding philosophies that remain relevant up to the present day.

2. Population pressures

China’s population has always had a high population, by 1840 it stood at 400 million - already about one third of today’s figure. Nearly all suitable land was being farmed and so there was a constant threat of famine. With so many people with little or no work to do there was no commercial benefit from mechanization; it was always cheaper to hire someone to do some work than to buy and run a machine. This was in contrast to Europe, where there was still untouched land to be developed and the cost of labor was significant. In the Industrial Revolution machines that tilled the soil and machines that weaved textiles made many workers redundant. In China there was violent opposition to the introduction of steamboats and railways as they removed employment from millions of already poorly paid people.

3. Central Imperial control

China’s culture was steeped in Confucian deference to ‘superiors’ and particularly the Emperor. To do things differently would challenge accepted thinking and so be seen as an unpatriotic and subversive. There was a general attitude of paternalism, people did not take action themselves, they waited to be told what to do by the authorities. They rarely innovated to solve problems as only officially approved inventions could be used. The centralization embraced study too, a mathematician who excelled at the examinations would always aspire to a court appointment not to work by himself or for a local nobleman. Sensitive subjects such as astronomy and mathematics could only be studied at court under Imperial auspices, independent study was not allowed. Matteo Ricci’s books on mathematics were confiscated on his arrival in 1601 as no-one apart from the designated Imperial scholars could study this important subject. Such a system did not provide for accepted opinion to be challenged or independent research to be carried out. In Europe there was more freedom to study what you wanted and there were always places where you could move to escape state interference.

In China it became a question of recording current knowledge and not looking for new theories. The Emperors had an unshakeable belief about Chinese supremacy and that there was no need for investigation into nature as everything was adequately explained by current thinking. This is rather like searching on Google only to find that every conceivable thing had been studied many times before, so what is the point of repeating research work? China had at several times in its long history put all knowledge into huge encyclopedias of hundreds of volumes. Scholars referred to these vast accumulations of knowledge rather than studying from nature afresh.

4. Middle class merchants

The Imperial system had the emperor micro-managing the whole nation. There was little local power and so the middle class was not very significant. In Europe it was the educated middle classes that developed studies of nature and set up new businesses. The independently wealthy could research whatever they liked. A ground-breaker in the UK was the Royal Society ➚ in London where the relatively well-off came together to discuss ideas and observations. In China it was only the Imperial institutions that carried out research. The social position of business people in China was very low - merchants were considered of lower worth than farmers - as they at least actually produced something useful. China considered agriculture the important aim of all endeavor as producing enough food for all the people was always a struggle. Free market commerce was restricted to only a few areas: silk, porcelain, salt and foreign trade. Indeed it was considered indecent to talk about wealth. Another factor limiting the development of independent business was that there was no infrastructure to support free market industry and commerce. To be able to set up and run a business needs banking facilities and corporate governance structures.

5. Locked in stasis

After a long period of study an agreed opinion becomes established that is very hard to shift. For many centuries Europeans looked back to Greek and Roman science and technology as a golden age, but by the medieval period this deference to ancient wisdom faded. Previously it had been pointless for anyone to challenge the science of Aristotle ➚ or the mathematics of Euclid ➚, the theories were just treated as the unalterable last word. The relaxation in the rigid belief in ancient wisdom did not take place in China. For example the Qing court astronomers could use calculations to predict orbits and eclipses but had no idea of the theory behind them because over the centuries the understanding of the underlying principles had been lost. The new European mathematics allowed the Jesuits to demonstrate their superior predictive skill to the Emperor. The generally admired Emperor Kangxi came close to embracing western mathematics and science. He was a personal friend of Adam von Schall and worked on a translation of Euclid's Elements ➚, however both internal missionary squabbles and Chinese conservatives put paid to this development and the Jesuits were expelled. It was the Imperial Examination system that was mainly to blame for the descent into stasis. Students who could recall information accurately were rewarded as it was geared to people learning the Classics by rote. Creative people with fresh ideas did not do well in the examinations. The prevailing, official Neo-Confucian philosophy was unchallengeable.

There was a general feeling that Chinese society had developed to a near perfect level and there was not much need for change – maybe only a few fine adjustments. Agricultural productivity had reached the maximum attainable before modern fertilizers and pesticides became available. The latest innovations brought in from Europe in the 18th century were seen as interesting toys of no practical value.

While it is true that Europe was leaping ahead in science and technology, to suggest China was standing completely still is a misconception. China continued to make fine innovations across many fields: drilling, gunpowder, ships, tunnels, cast iron and the bridge building. For example the latest food crops of sweet potatoes, maize and peanuts imported from South America were quickly included in the diet.

What goes unchallenged in this debate is that China lost out to a superior set of ideas; but this must be questioned in the light of the current world situation. Economic and population growth can not go on forever; it is a finite world with finite resources. Surely sustainability must be the guiding concern? China of the nineteenth century had reached a relatively static but sustainable level of development. China was self-sufficient and for many centuries relatively peaceful and prosperous. Only time will tell whether rapid industrial and technological development fueled by modern scientific understanding was the correct direction to take; may be China took the right course rather than following the West in its mad dash to exploit the planet.

6. Second class science

China always valued the humanities above the sciences. If you aspired to high office it was the classics rather than the sciences that you would study. In China the Daoists studied nature but it was the Confucians who formed the ruling elite. Confucians had a low opinion of Daoist teaching as something for the illiterate masses and this had a negative impact on scientific research. Daoist analysis was fairly superficial, involving observation and reflection rather than taking things apart and trying to answer the fundamental ‘why?’ questions. Many Daoist texts are full of wonderment at the structure of nature without seeking to explain how it came to be. The primary concern of Chinese administrators was the health and welfare of people rather than increasing knowledge. Science for science’s sake was not thought of as a useful occupation as it did not directly benefit anyone. It was considered more worthwhile to study ethics and politics that could enhance everyone’s well-being. By contrast in Europe the ancient studies in sciences (nature, mathematics and philosophy) retained a high status.

7. Glass

Some have taken the view that the stalling of Chinese scientific development was purely down to just one thing - glass. Although China used a small amount of glass for decoration it did not use it for windows or drinking vessels because paper and porcelain were used instead and so China did not develop processes to produce high quality glass. It has been said that the European skill in making fine, clear glass made all the difference because you need quality glass to make lenses. Lenses are used in both microscopes and telescopes and these instruments open up vast areas for scientific study. For example the early microscopic images of a flea by Robert Hooke in 1665 caused a great deal of wonderment and excitement and provoked much new study of nature. Similarly the observation of Jupiter's moons by telescopic lenses led to new planetar theories. Just as significantly glass lenses for spectacles allow scholars to study well into their old age.

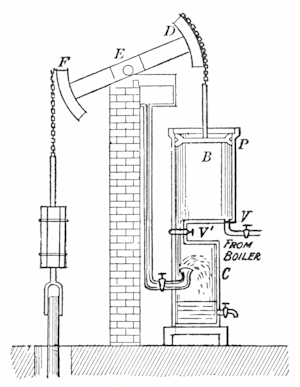

8. Fueling the revolution

While glass may have been one material influencing development another was coal. Although China has plenty of coal, most of it is not exposed at ground level and has to be mined. New machines (weaving, pumping and locomotion) all needed fuel. Without access to coal, timber had to be used and China had a severe shortage of this fuel after centuries of deforestation. With timber so scarce and expensive, new machines were uneconomic to run. At Ironbridge ➚, UK where the Industrial Revolution is said to have begun, there was coal, limestone and iron ore all readily to hand; Abraham Darby could easily use the natural resources to set up the mass production of cheap iron.

9. Far flung lands

By around 1800 the European nations had begun to establish overseas empires in Africa and the Americas as well as Australasia. The colonies had an invigorating effect on the Industrial Revolution. They provided new untapped resources: labor, food, oil, coal, fertilizer and many raw materials that fueled the rapid development of European states. Manufacturers were also able to exploit new markets for their products. To conquer and control these territories required a professional army with superior weaponry. Enterprising Europeans could move to the colonies and start up new businesses with the support of their governments but with little interference. On the other hand China had no official colonies and the standing army was only used to maintain internal order. China continued to trade very widely, but she did not occupy land overseas.

10. It’s the economy, stupid

For much of the Qing dynasty the government’s finances were in a poor state. There was just no surplus to plow into exploring new technologies. In Europe, by contrast, a virtuous economic cycle was in operation: technology and innovation fueled economic growth which provided the funds for technology to be developed further. Although China was initially able to amass wealth from selling tea, the tables were turned when Europe, and Britain in particular, began to trade in opium. The scale of opium addiction in China destroyed any chances of economic reform or scientific advances.

11. Dynastic cycle

For thousands of years China has been ruled by different dynasties that went through a cycle of change. On foundation a dynasty would re-invigorate the whole country with reforms; which would then be followed by a period of consolidation with relative peace and prosperity. The final phase is of decadence, complacency and decline. Weakening central control led to revolts that swept a new dynasty to power. China in the 19th century was entering this last phase.

There were opportunities for change in the failing days of the Qing dynasty. The Taiping Rebellion (1850-64) overran all of southern China and could easily have captured Beijing and overthrown the Manchu rulers had they wished. The strange mixture of western and Chinese philosophy adopted by the Taipings would surely have reformed Chinese society and scientific work in particular. The ruinous death toll, expense, and damage of this rebellion took away any possibility of fundamental change thereafter. Belated Qing attempts at reform : The Hundred Days Reform and Self Strengthening Movement were too little, too late. Any moves by Han Chinese to keep the ‘foreign’ Manchu dynasty in place were met with opposition particularly in the south.

12. Linguistic limitations

Some scholars believe that it was the limitations of the Chinese language that prevented progress. If a language can not express concepts clearly it can become a severe obstacle. This idea is rather disproved by the fact that complex logical thoughts as set out in Euclid or Aristotle were able to be translated into Chinese without great difficulty. While it is true that many Chinese characters have multiple meanings which could make texts ambiguous, in actual fact this is not a problem in practice. Perhaps the very formal nature of the literary language used by scholars was an obstruction, but this is mainly because so few people could read and write this form of the language rather than a limitation of the descriptive power of the language itself.

13. Racial characteristics

It has to unfortunately be admitted that for years the general western perception was that the Chinese race were considered ill suited to scientific research and development. The American missionary Arthur Henderson Smith (1845-1932) wrote of the mind of a Chinese man: “He knows nothing about logical contradictions, and cares even less. He has learned by instinct the art of reconciling propositions which are inherently irreconcilable by violently affirming each of them paying no need whatever to their mutual relations”. Events have proved this view wholly incorrect. China’s space exploration program is as ambitious as America’s and it boasts world class radio telescopes and particle accelerators. There is no field in which Chinese science and technology is now, if not leading, at least of world class.

Conclusions

Some have taken issue with Needham's question on the basis that it is far too simplistic. How can all the events of China and the west leading to the divergence be sensibly compared? What is meant by 'development', is it just industrial use of technology? In which case China had modern techniques for example in the Jingdezhen potteries long before the Industrial revolution. Or is it the reliance in China on empirical studies rather than pure, abstract mathematics as developed in the west? Even though the question is in itself somewhat flawed it is interesting to speculate on the key factors.

All these proposed answers to the Needham question, except the last one (13), do seem to have some merit. It would be easy for me to conclude by saying that no single factor wins out and that the true answer is some combination of them. If I am forced to choose the best candidate to answer the question it must be (5) ‘Locked in stasis’. Having recently read Lao She’s thought provoking book ‘Cat Country’ it is hard to escape the fact there was in the early 20th century a sense of being trapped by tradition, locked into orthodoxy because that was how everything had always been done. The lessons of the Republican period (1911-1949) also sheds some light; reforms were introduced, western science was taught and western factories built but these attempts at change never took firm root and failed to prosper. I put this down to a defeatist attitude that had inviegled into all layers of society - that there was no point in trying to modernize, it was all bound to fail. Only the re-invigoration of national spirit that came with the foundation of the People’s Republic in 1949 was the necessary self-belief created that China could still succeed in the modern world. It is the underlying aspiration of people that ultimately makes all the difference. China had truly stood up.