Chinese Painting : 中国画 Zhōng guó huà

Many weighty books have struggled to cover the whole, long history of Chinese painting so here is only a brief summary. We’ve arranged our overview in three sections: historical development; styles and techniques followed by profiles of some leading painters.

Calligraphy and painting have always been the paramount art-form in China. Painting is almost always water based rather than using oil or other media. Painting is learned much like calligraphy, first the technique for drawing individual elements is mastered and then these are put together following common guidelines. An artist should first have wide knowledge before beginning to paint from the study of books and extensive travel.

The first reaction of westerners to traditional Chinese landscape is often to say it does not look ‘realistic’. However, it has always been and remains the aim of the Chinese artist to capture the essence or internal energy of something (its Qi) which goes beyond a mere photographic likeness. A photograph captures just one instant of time.

A brief history of Chinese Painting

Early painting

Before about 600CE very little has survived because painted surfaces (paper, wood, silk and fabric) have decayed. However designs painted on ancient pottery have been discovered that take the story back into prehistory.

Han dynasty 206BCE - 220 CE

From the Han dynasty we only have some fragments on lacquered wood and silk. On the tomb of Wangdu ➚ 182CE some frescoes of hunting scenes have survived.

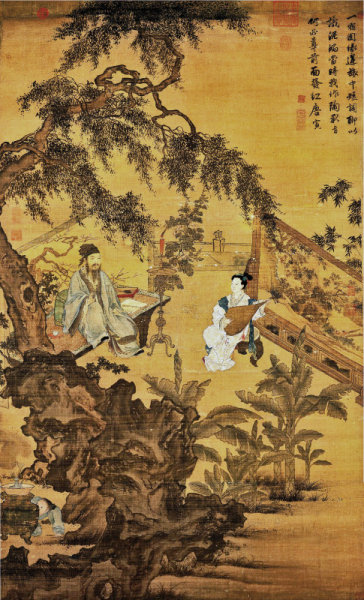

From this period onwards an aspiring scholar was expected to be proficient in the four arts: poetry, calligraphy, music and painting. Evenings would be spent among government officials using whichever art medium could best express their feelings at the time: writing a poem, playing some music or painting a picture - the arts overlapped for 2,000 years. The paintings of the literati scholars were for the appreciation of friends and rarely kept permanently and never sold.

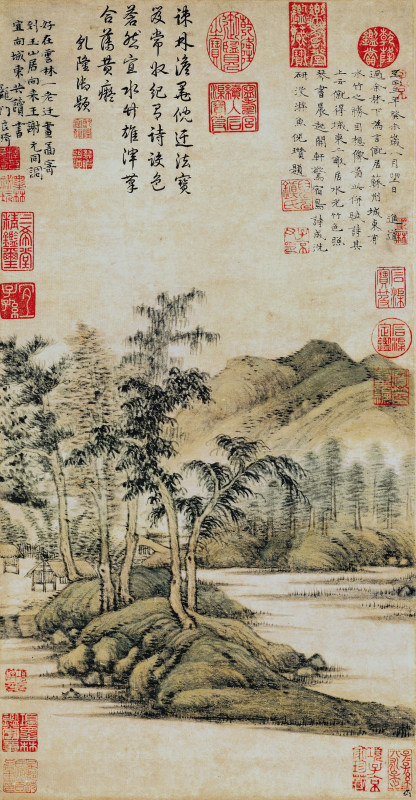

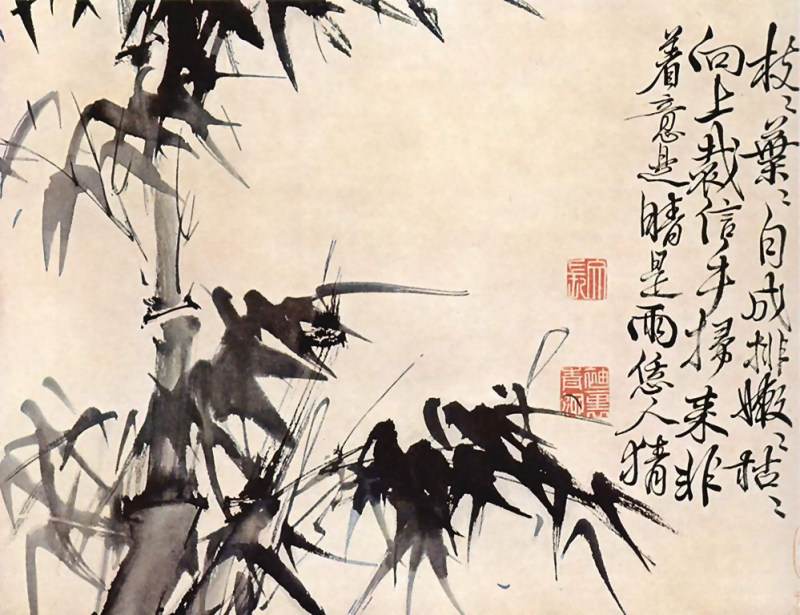

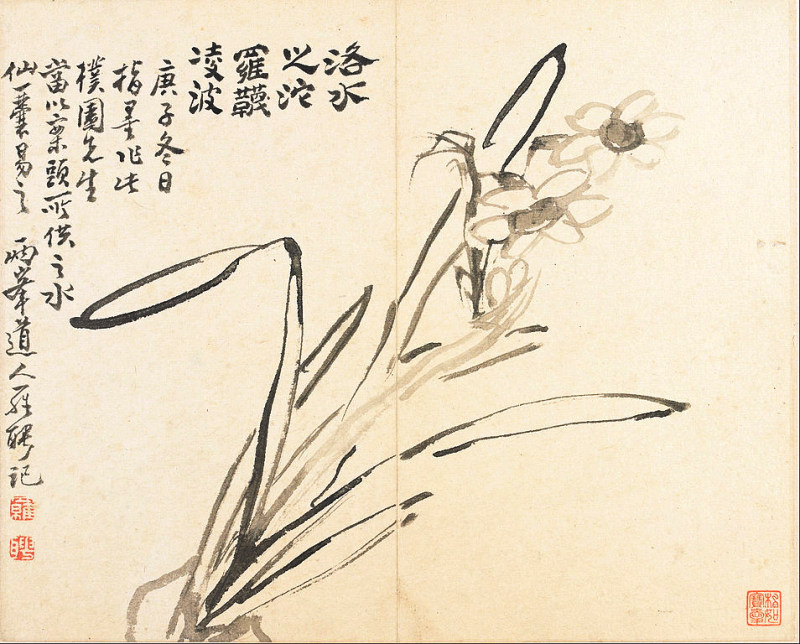

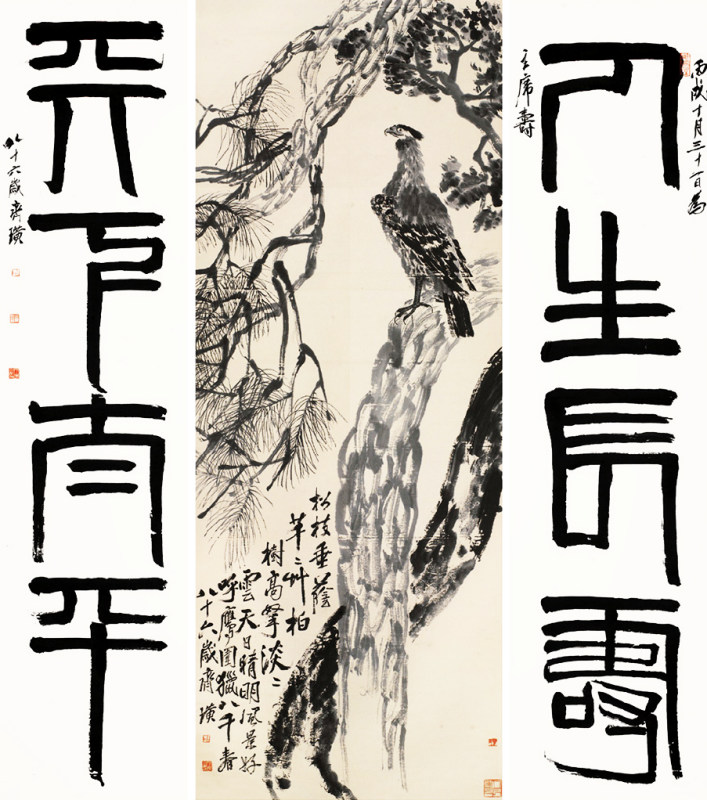

It was also from this time that the use of a brush and black ink on paper emerged as the dominant painting style as a clear offshoot from calligraphy - the same brush and ink were used for both. The use of paper and ink had a persistent influence on style from then on. Once a mark is made it cannot be erased unlike the western tradition of oil painting. To achieve smooth lines the brush has to move fast and this leads to carefully planned and rather sparse compositions.

Tang dynasty 618 - 907

Painting continued as the hobby of educated scholar-officials. By this time the main ‘schools’ of painting style had developed. In fact at this early stage there was already a standard method to paint subjects like bamboo, birds, trees, rocks and mountains which has been followed by many painters ever since.

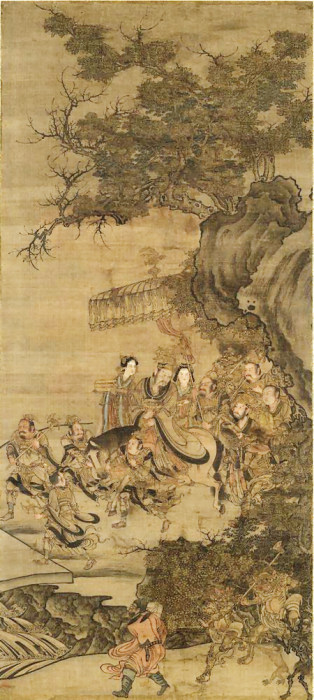

The influence of Buddhism was significant as now human figures were extensively painted and sculpted. Some artists took to drawing graduated color tones to give a life-like image to figures but this trend soon disappeared. In the safety of the caves at Dunhuang a large number of paintings have survived including elaborate frescoes. They show strong Indian influence and not representative of art in eastern China. The repetitious nature of Buddhist mantras is also evident in the accurate copying of Buddhist figures. When Buddhism was suppressed in 845CE many paintings were destroyed.

Emperor Xuanzong was one of the most famous painters together with the poet and painter Wang Wei who produced vigorous monochromatic scenes. Wang Wei’s paintings have survived only through later, careful copies of his work and these strongly influenced painting thereafter.

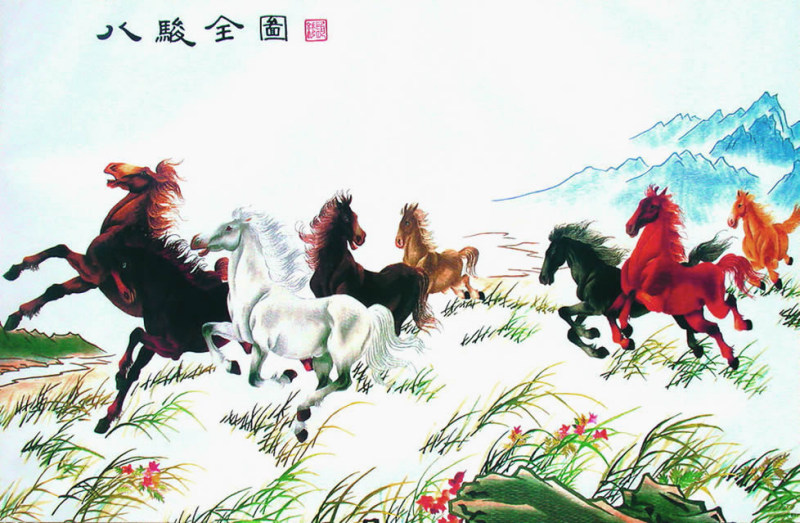

The leaders of the Tang dynasty came from horse riding tribes on China’s northern-western border and the painting of horses became a popular subject at the imperial court. In particular Emperor Taizong's love of horses led to many sculptures and paintings of them being produced. Taizong also set great store on calligraphic style and appointed officials on this basis of writing rather than knowledge.

The murals at the tomb of Princess Yongtai ➚ (685-701) in Shanxi provide a good example of Tang wall painting. Most Tang paintings were in the form of wall decorations. Few originals have survived but copies, believed to be accurate, have done so.

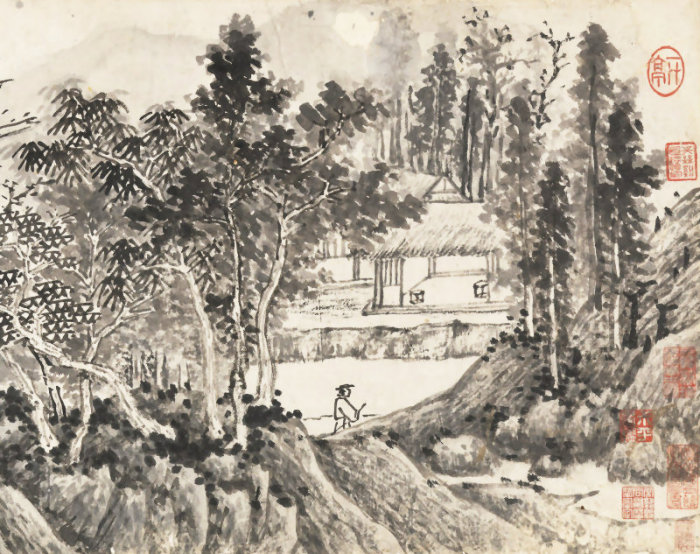

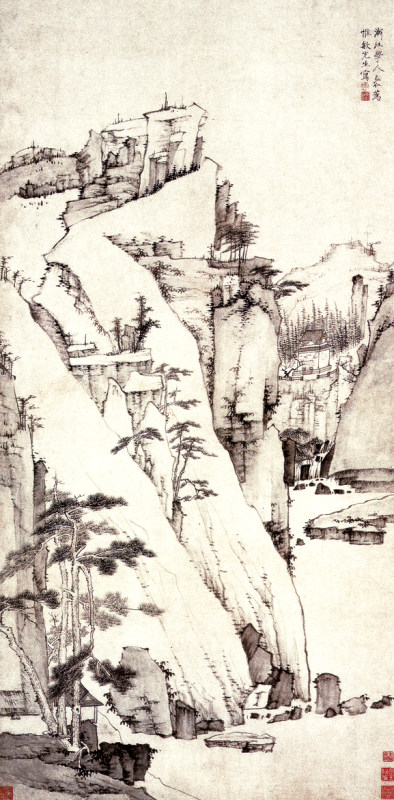

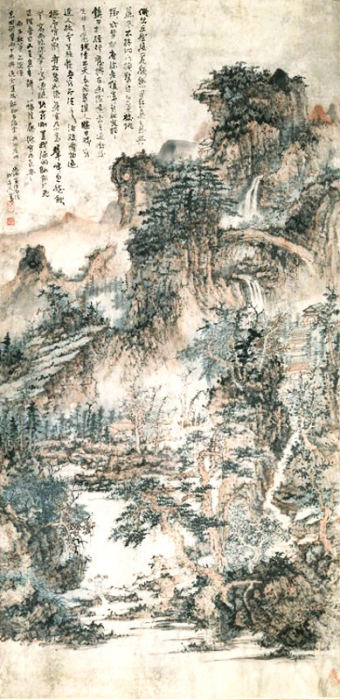

In landscape painting the characteristic Chinese style had developed. Remote landscapes were painted with exquisitely detailed work of towering rocks and clouds became the norm. These scenes of idealized scenery with a sense of perspective developed long before western landscape painting. As many were based on recollections of journeys they allowed the painter to relive experiences out in the mountains. The gradual shift from figure to landscape painting has been said to mirror the resurgence of Daoism.

There were a good number of experimentalist artists who used all sorts of weird methods of applying paint, including painting to music and painting without seeing the brush.

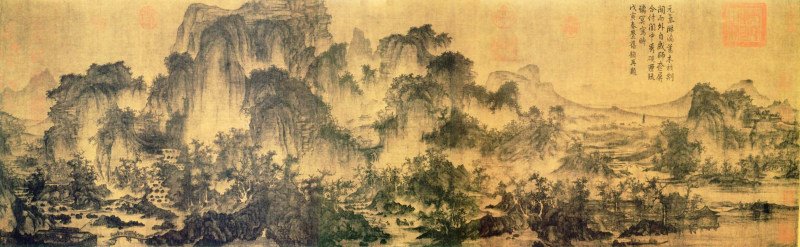

Song dynasty 960 - 1279

The Song saw a flourishing of all the arts. In painting there was a strong influence from the imperial court. To be a successful artist the patronage of the emperor was crucial. Emperor Huizong was himself a noted artist as well as calligrapher. He concentrated on producing very accurate life-like representations of flowers and birds. He was an avid collector and amassed 6,396 paintings by 231 artists in his collection from as far back as the Han dynasty. The artist Li Tang strengthened the tradition of landscape painting. The flourishing of different schools of landscape painting styles occurred during the Song particularly landscape and nature subjects.

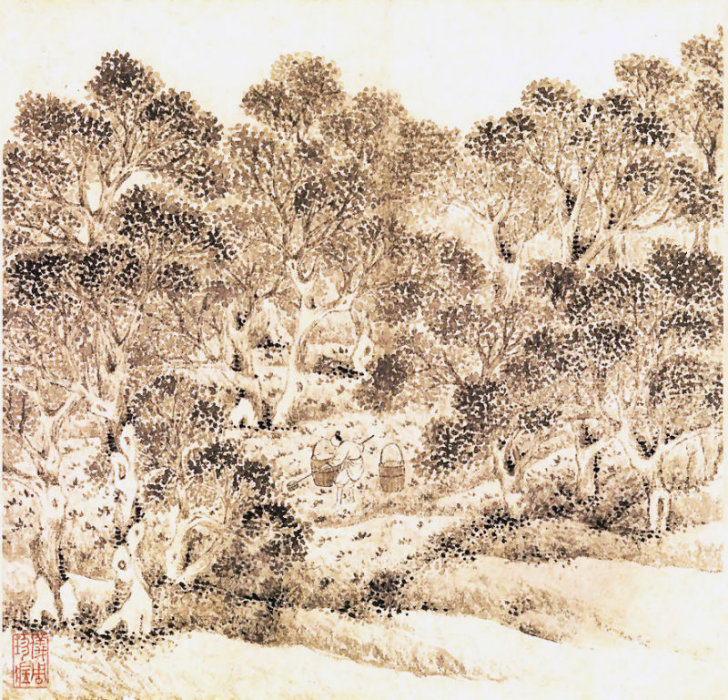

The general trend was to move away from detailed realism to more expressive and sparser brushwork. Some painters experimented with a pointillist style where the whole painting is made up of just dots (many hundreds of years before artists like Seurat ➚ in the west).

The most famous painting in China is the Qingming Festival (10" x 16ft) by Zhang Zeduan (1085-1145). This intricate ink drawing on silk teems with everyday life in a naturalist setting. The scene is the bustling capital city of Kaifeng (or 汴京 Biàn jīng) including shops, ordinary people not just imperial officials and soldiers as well as a bridge and fields. It was much loved by the last Emperor Puyi who took it with him when fled the Forbidden City in 1924. It was then lost for a while but found again 1950 and now kept at Beijing. Unlike the prevalent painting style it uses accurate perspective across the whole painting.

The more impressionist landscape style of painting continued. Mi Fu (1051-1107) was a great calligrapher as well as painter and used his skills to capture the mountainous landscape of the lands south of the Yangzi.

When the dynasty was forced to move to southern China the paintings became smaller and of a more intimate style - reflecting a retreat into nature. Figures are observers on a scene evoke a sense of loss now that northern China had been overrun by the Jin.

Many paintings were made on scrolls and this influenced the style. As the painting was gradually scrolled through new scenes come into view. This created a dynamic painting with a narrative and is one reason why paintings have blank areas as this allows one scene to smoothly transition to the next. The same figure may be seen in different ‘scenes’ within the painting. The tradition was not to hang paintings permanently on walls, they would be taken out and admired on special occasions.

The paintings made by scholars as an evening hobby have rarely survived. There is evidence that many used an expressive, experimental style to capture a particular element of a scene rather than a complete ‘finished’ painting. The fruits of experimentation influenced the professional painters.

Many consider Song landscapes, in common with their porcelain, unsurpassed. They manage to evoke awe and splendor. Calligraphy was of a high standard and was considered very expressive - a 心印 xīn yìn ‘heart image’.

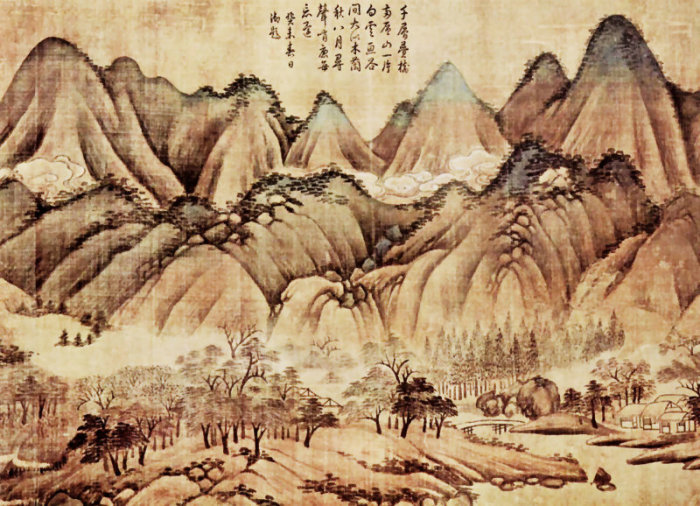

Yuan dynasty 1279 - 1368

Some painters in the south around the former capital Hangzhou continued much as before (such as Qian Xuan) including the ‘Four Yuan masters’ Huang, Wu, Ni and Wang. Qian Xuan and others went to the new capital Dadu (Beijing) and were influenced by the Mongol taste for more figurative subjects. A tendency to look back to the Tang dynasty to recreate favorite images took hold with graded washes replaced by flat ones. Landscapes typically show only a few distant figures.

Tāng hòu 汤垕 wrote a treatise on art ‘古今画鉴 Gǔ jīn huà jiàn’ in around 1320 in which he expressed the aim of painters down the ages:

“Follow your heart without constraint and your brush will be inspired.Writing and painting have a single purpose: the revelation of virtue.

Here are two friends: an old tree and tall bamboo,

Changed by his free hand, completed in an instant.

The spirit of a transitory moment is treasure for a hundred ages

You feel, as it is revealed, a fondness as if seeing the artist himself.”

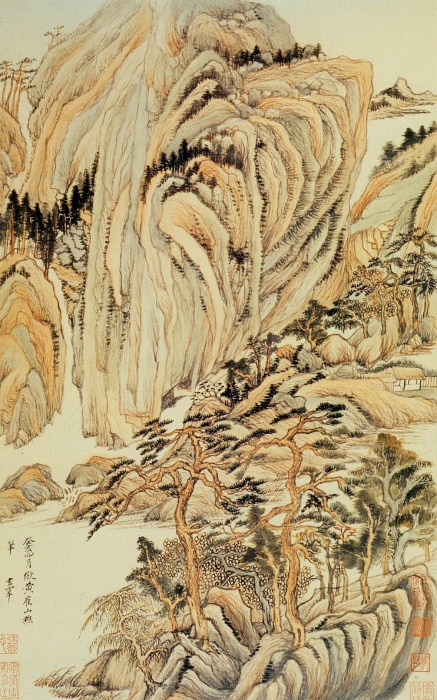

Ming dynasty 1368 - 1644

Although the Ming dynasty saw some accomplished painters who introduced further refinement of technique the range of subjects declined rather than increased. The Emperors revived the courting of leading painters in an attempt to match the glories of the Song and Tang dynasties. Painters concentrated on learning from the work of previous great masters rather than developing their own individual styles. Dong Qichang was influential in putting all art into well defined categories and this suppressed experimentation. Although the detail is impressive somehow they often fail to capture the essence that the Song painters achieved, for example birds look static, nailed to a perch and the composition is cluttered. Being a painter became a profession rather than a scholarly hobby and this affected the range and quality of work. Hu Zhengyaman’s ‘Ten Bamboo Studio Manual of Painting and Calligraphy’ remained a classic for 200 years.

The ‘Wu School’ centered at Suzhou produced some great artists separate to the Imperial court. In the middle Ming only a few isolated painters are considered of sufficient artistic stature to have created worthy paintings. There was only limited innovation (such as Xu Wei and Zhang Feng) and those that did not gain popularity at the time.

Qing dynasty 1644 - 1911

The tradition of honoring the glorious painters of the past continued with less innovation. The ‘Four Wangs’ were important painters of the early period. Emperor Qianlong was a very active collector of art who built up a huge collection. Some painters, such as Gao Qipei, retired from court life to pursue their love of painting and they made some contributions as individuals apart from the rather moribund mainstream. The ‘Eight Eccentrics of Yangzhou’ formed an influential group - although there were actually eleven in the group. The influence of European styles began but had limited effect, mainly because paintings produced for export to Europe had to be made in the expected ‘Chinoiserie’ style.

Republic of China 1912 - 1949

With the collapse of the imperial system the system of patronage broke down. Many artists went to study and live abroad and new styles were developed. Gao Jianfu was one of the leading painters of this time. Xu Beihong became very famous for his depiction of horses in movement.

Peoples Republic 1949- Present

During the fervent era of communist reforms only subjects of toil in the countryside were acceptable. The austere landscape and photo-realistic capture of nature were seen as decadent. The possession of old paintings and books was dangerous and could earn a spell in a labor camp but modern paintings still used brushwork and the reverence for fine calligraphy continued. The ‘peasant’ naive painting style was heavily promoted with its scenes of rural life.

It has been only really been since about 1990 that appreciation of ‘traditional’ subjects has returned with paintings by old masters commanding very high prices. There are now many artists experimenting with a fusion of western and Chinese styles.

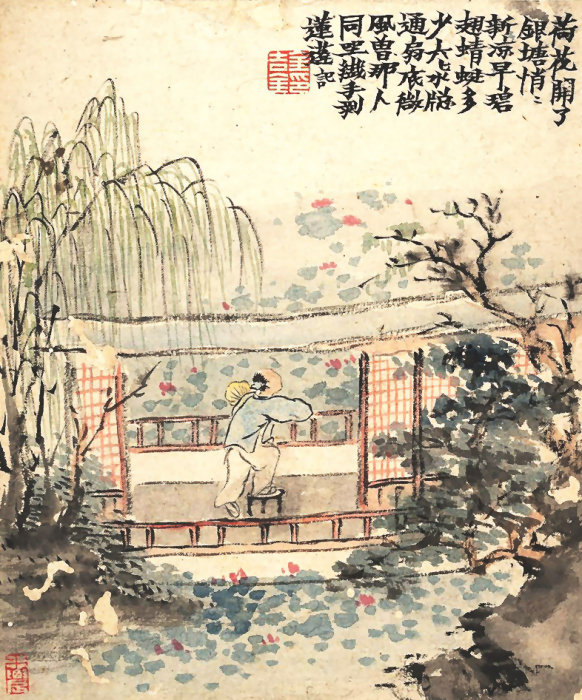

Painting styles

Painting and Calligraphy are strongly linked as both use the same brush and ink. Often calligraphy is valued above painting as after all the same brushstrokes are used. The artist frequently wrote one of his poems on his paintings. The style and content of the poem should be in harmony with the painting; they are not an independent adornment. The calligraphic skill for shaping characters is evident in the similar marks used in painting - particularly dots and swirls. Generally traditional painting does not show shadows - subjects are as seen straight-on; this style is somewhat dictated from the use of the brush as graded shadows are much harder to draw/paint than outlines.

Subjects have over the centuries included just about everything: immortals, historical figures, architecture, plants, animals and of course landscapes.

Over the centuries detailed rules emerged which were slavishly followed; they proscribed for instance how to paint mountains in any season or weather and where to place towns and buildings in the landscape.

Xie He [6th century] wrote a very influential ‘six principles of painting’ 六法 Liù fǎ that held for many centuries. These are:

- Lively movement 气韵 Qì yùn The painting should not be a static scene but give the impression of movement.

- Bone movement骨法 Gǔ fǎ. Painting strokes need to be firm and solid.

- Form from nature 应物 Yìng wù. Study of nature is paramount in absorbing the essence of a scene.

- Tonal harmony 随类 Suí lèi. The layers of tone and color should harmonize.

- Composition 经营 Jīng yíng. The painting should be balanced.

- Copying 传移 Chuán yí. Learning from the old masters.

Copying

It is the last of these that has perhaps held back Chinese art because in the Ming and Qing there was too much slavish copying of old masters. It lost the aim of copying a master as a tribute or a learning exercise. Painters was praised for how accurately they copied a master. Many painters were lauded for making a perfect a copy of a great painting. To achieve a good copy it’s necessary to understand the original painter’s technique and mindset.

An artist will progress from unskilled (unable to produce a likeness of nature) to skilled in copying and then finally to be unskilled again so nature is expressed but not as a straight copy. You have to learn how to paint accurately before being able to express the hidden essence that cannot be directly seen.

In the west ‘copying’ is now considered a ‘bad’ thing but not so long ago European artists would learn their trade by copying great paintings of the past and often belong to a ‘school’ that specialized in one particular artist’s style. Nowadays this is seen as cramping people’s style and innovation.

Balance

A good Chinese painting is balanced and not just in simple compositional terms. This is part of the eternal quest for harmony between yin and yang. The whole painting needs to be consistent in use of style. Here are some of the spectra which an artist must somehow seek to harmonize.

Elegant - Vulgar (雅 Yǎ - 俗 Sú )

A painting should aim to be elegant. It is vulgar if too ‘sweet’ (kitsch) or too obvious a copy. ‘Vulgar’ paintings however have their place too.Raw - Ripe (生 Shēng - 熟 Shú)

A painting must find its balance between being spontaneous ‘rough or raw’ and being formal ‘labored or ripe’. Getting the precise level correct between these two extremes is tricky to learn and teach.Clever - Awkward (巧 Qiǎo - 拙 Zhuō)

A balance between looking too clever or too awkward. A very refined, formal painting can be unexciting but awkward, crude, spontaneous brushwork can be very expressive. Su Dongpo wrote ‘It is not artistic skill that is hard to achieve but awkwardness’.Heavy - Dynamic (重 Zhòng -大 Dà)

A painting can be ‘profound’ by using deep, dark areas or more ‘dynamic’ by use of large, open spaces with sparse strokes.The ritual of painting

Painters need to develop the correct mindset before starting to paint. Everything should be carefully set ready. Traditionally this involves the slow grinding of the ink-stone to create the ink and this process acts as a meditation. Just as there is a proper way to prepare tea there is a proper way to prepare to paint.

Imperial patronage

To make a living as an artist rather than as a hobby really required patronage and in China the emperor was the most important patron. As painting was considered one of the chief accomplishments of a civilized man the emperor took personal interest in painting. However many emperors viewed painting as a craft rather a creative art and artists were told precisely what to paint and in which style. The artist’s freedom of expression was very limited and many innovations came from artists who were exiled or retired who could then paint what they wanted.

The imperial, rather formal style is called 院画派 Yuàn huà pài with emphasis on achieving a perfect form. In contrast is the concept of 写意 Xiě yì or simplified school of more impressionist style with far fewer brushstrokes.

European style

After 1600 there was some contact between European and Chinese painters. Some of the Jesuits were artists and brought artworks from Europe with them.

The main difference was that Europeans had now mastered ‘photographic’ likeness in portraiture and landscape by use of perspective and shading in oil paint. To the Chinese they were seen as interesting tricks akin to “trompe l’oeil” but not true art as they do not express the painter’s appreciation of the subject. The Jesuit frescoes at the Beitang cathedral, Beijing attracted many admirers. They were not seen as similar to Chinese art and had little influence on artists. Contact with European artists was very limited and Europeans viewed the Chinese paintings as too abstract - ‘photo-realism’ at the time was all that mattered.

Perspective

One of the most obvious differences in Chinese art is the use of perspective. From early days the style rejected realism that accurately follows perspective lines. A painting should not show a fixed viewpoint and in this way is allied with cubism ➚. Freeing an artist from seeing a scene from just one place greatly widens the choice of possible compositions. Some describe Chinese landscape perspective as ‘bird’s eye’ or ‘aerial’ as the viewpoint looks down on a foreground with the mountains forming the background. Several ‘views’ can be combined in one painting. This technique was pioneered by Guo Xi a thousand years ago.

Portraits and figure painting

This style became dominant during the Tang under the influence of Buddhism where figure painting is part of the custom. It dwindled by the time of the Song and was thereafter not a major school. The style of portraiture was to draw the figure ‘flat’ without shading.

The Buddhist style of painting continues to this day in Tibet. The Thangka Tibetan painting tradition is painted or woven on silk, cloth or canvas. The later style shows mainly historical scenes and Buddhist customs.

Qing Emperor Qianlong hired the European painter Castiglione ➚ to paint in the more photo-realistic style used in Europe making use of shadows to create a more life-like image but this was only a short term fad.

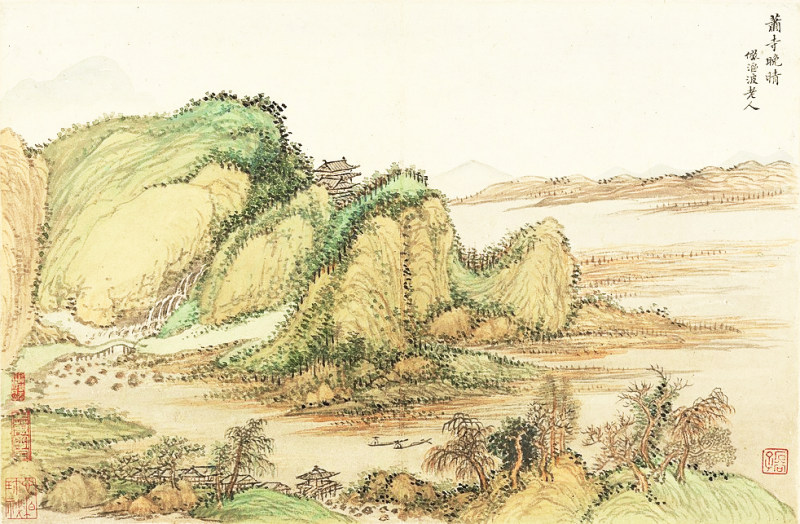

Landscape painting

The Chinese for landscape is 山水 shān shuǐ mountains and water which encapsulates the content of traditional landscapes. Dominated by mountains the composition levels out to a river or lake to maintain the balance of yin (water) and yang (mountains). The high mountains look exaggerated but accurately reflect the rugged terrain of central and western China, for example the strange mountains around Guilin. The dominant mountain is ‘yang’ and grounds the whole painting with much else is ornamentation. Mountains take us closer to the heavens and paintings can achieve the same feeling. Many landscapes are an artistic fusion of different scenes and perspectives carefully woven together.

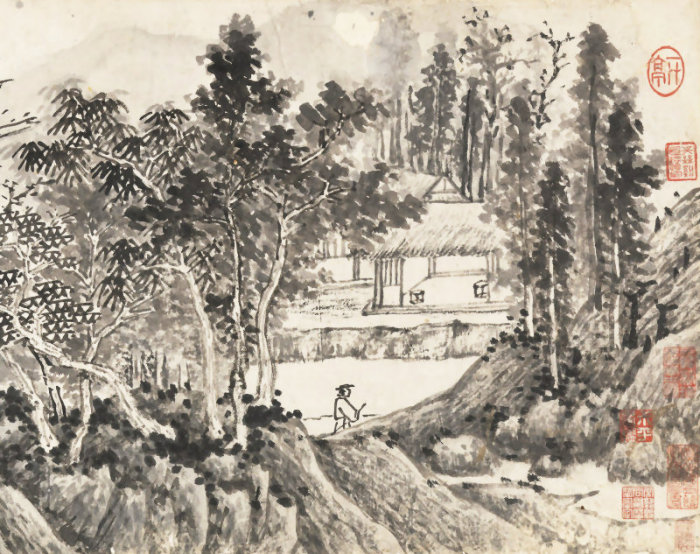

Large areas of empty paper are left honoring the Daoist concept of ‘emptiness’ while serving the useful purpose of transition to a different scene or viewpoint.

Human figures are sparse, small and distant. The effects of human habitation are kept to a minimum - a few houses and gardens but no fields or villages. This style began around the time of the Tang and has been the dominant style for much of the last 1500 years.

A painter spent time studying the landscape at first hand and then when the scene had been fully absorbed only then was it painted at home in the studio.

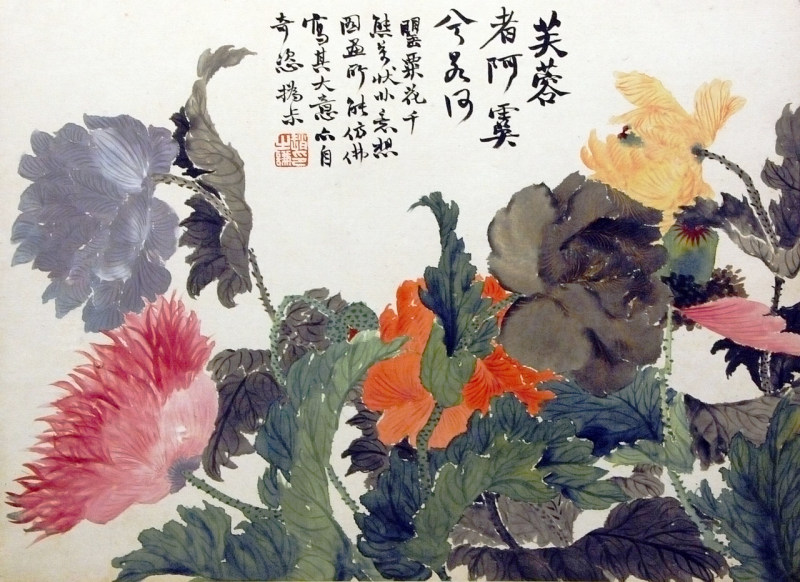

Nature subjects

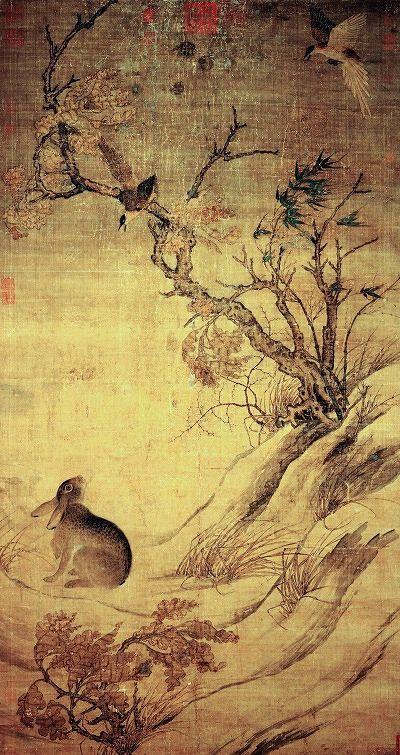

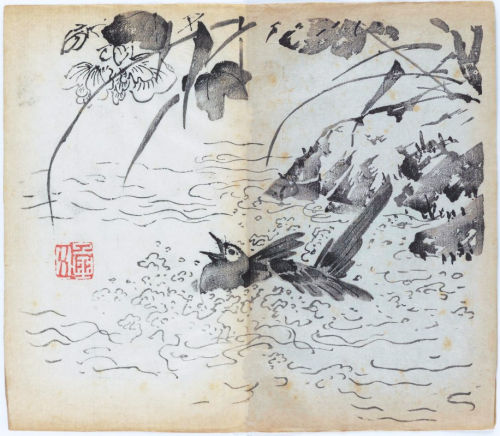

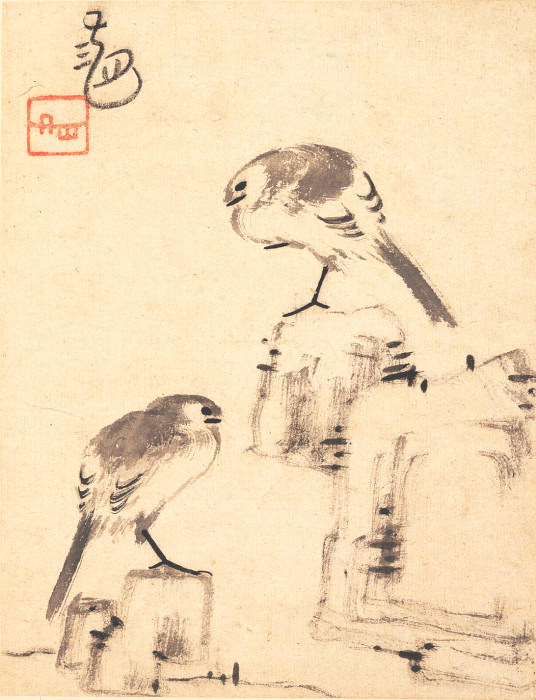

Birds, insects, fish, animals and flowers have been popular subjects since around the time of the Song dynasty. The more painstaking techniques are used to give a realistic rendering. Animal subjects are shown in active postures - not a static pose and rarely looking at the painter. For example Cui Bai’s ‘Hare and magpies’ (1061) shows a hare looking back at two magpies mocking it. Song Emperor Huizong set the style for bird and flower painting in which he lauded realistic, accurate imagery.

Symbolism of plants and animals is very important and the choice of subjects provides a hidden message. The aim is to bring out the spirit of the subject in a natural way. The painting of bamboo is particularly important. It is strong but supple and the foliage sparse. It provides many opportunities for learning particular single brushstrokes for leaves and stems.

Nature subjects often use color rather than the monochrome palette of most landscapes.

Significant Artists up to 1950

With such a long recorded history there are many thousands of known artists. Only a short selection of the most influential has been selected here in order of year of birth. We do not cover living artists.

Gu Kaizhi 顾恺之 [c.340-406]

Renowned as a bit of an eccentric but in his painting he was fairly staid and conservative. Best known for figure painting and mainly through copies. His best known painting is the ‘Admonitions of the Court Instructress’. He also painted some of the earliest known landscapes in the Chinese style.

Zong Bing 宗炳 [375-443]

An artist who wrote the earliest known book on landscape painting. Artist details… ➚Zhang Sengyou 张僧繇 [c.490-540]

An example of an early painter influenced by Buddhist painting style from India. Unusually figures are given a 3-D look by using graded rather than flat washes of color. He uses anatomically correct portrayal of muscular arms and legs. This style did not survive long after the Tang. Most of his art-works survive as wall paintings. Artist details… ➚Xie He谢赫 [6th century]

Famous for writing the very influential six principles of Chinese painting. Artist details… ➚Yan Liben 阎立本 [c. 600-673]

He was an architect, painter and official in the early Tang. One of the earliest Chinese paintings to survive is his ’Thirteen Emperors Scroll’ showing a selection of earlier emperors. Artist details… ➚

Li Sixun 李思训 [651-675] and son Li Zhaodao 李昭道 [early 8th century]

Considered the founder of the northern landscape school. Painted meticulously and in color. Developed landscape perspective of foreground and distant mountains. Artist details… ➚

Wu Daozi 吴道子[c.685-759]

One of the greatest painters of the Tang dynasty. He painted landscapes and figures and pioneered the use of large strokes of ink. Many murals that he painted have been lost. Artist details… ➚

Wang Wei 王维 [699 -759]

A poet and painter whose influence lasted five centuries. Around 400 of his poems survive but only copies of his paintings. Regarded as the founder of the southern school of landscape painting and as a pioneer of graded monochrome painting (破墨 Pò mò ‘layered or broken ink’) Artist details… ➚

Zhang Xuan 张萱 [713-755]

Specialized in the painting of the women at court. ‘Ladies preparing newly woven silk’ is his most famous work. He used color but in flat washes. Artist details… ➚Zhou Fang 周昉 [c. 730-800]

Mainly known for producing fine figure paintings for the Tang imperial court. Artist details… ➚Huang Quan 黃筌 [903-965]

An important court painter who specialized in accurate bird and flower paintings while at Chengdu, Sichuan. Artist details… ➚

Li Cheng 李成 [919-967]

Known for impressive landscape with fading grays to capture rocks and trees. Regarded as one of the greatest landscape painters. Artist details… ➚

Zhou Wenju 周文矩 [mid 10th century] (or Chou Wen-chü)

A famous figure painter who followed the style of Zhou Fang. Artist details… ➚Shi Ke 石恪 [10th Century] (or Shih K’o)

Famous for a rather abstract sketchy picture of ‘Two Patriarchs in Contemplation’ - an old man dozes on the body of a tiger. Individual broken brushstrokes make a very expressive picture; it is grounded in Zen Buddhism. Artist details… ➚

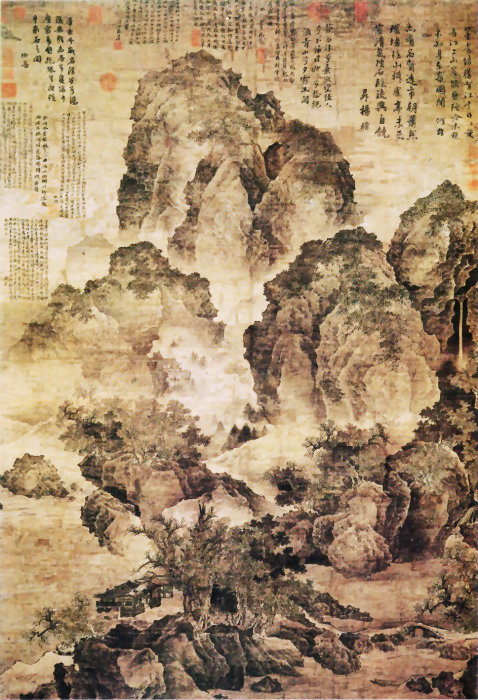

Fan Kuan or Fan Zhongzheng or Zongli 范宽 [c.960-c.1030]

A significant early Song landscape painter of the mountains of northern China. Artist details… ➚

Cui Bai 崔白 [11th century active 1050-80] (or Ts'ui Po)

One of the early specialists in bird and animal painting. Artist details… ➚

Guo Xi 郭熙 [c.1020-c.1090]

An important pioneer of multiple perspectives in landscapes in the northern Song dynasty. ‘Early Spring’ 1072 is a good example. The mountains are ‘unrooted’ and a series of scenes are fused together. Artist details… ➚

Li Gonglin 李公麟 or Boshi 伯時 [1049-1106]

Famous for drawing figures and horses. Artist details… ➚

Li Tang 李唐 [1050-1130]

One of the influential founders of the Southern Song style of painting. Known for forbidding landscapes, figure and horse painting. Followed the tradition of Fan Kuan. Artist details… ➚

Mi Fu 米芾 [1051-1107]

Painter, poet and calligrapher. Famous for painting the mountainous landscape south of the Yangzi. Artist details… ➚

Emperor Huizong 宋徽宗 [1082-1135]

A passionate supporter of all the arts and a very good artist in his own right. He liked to paint birds and flowers in naturalistic settings. Artist details… ➚

Liang Kai 梁楷 [c.1140- c.1210]

Sometimes known as ‘mad Liang’ for his eccentric and individualistic style. He pioneered a move towards minimalism, achieving impressions with minimal amount of brushwork. The character of human subjects are indicated by the style of brushstroke. The ‘Sixth Chan Patriarch’ is one of his most admired works as well as a portrait of Li Bai and a bamboo cutter. Artist details… ➚

Ma Yuan 马远 [c.1160 - 1225]

One of the leading Song dynasty court painters. With Xia Gui he formed the Ma-Xia school of painting. Known for dreamy sparse scenes where an official gazed towards hidden mountains in mist. Paintings are minimalist - pared down to essential elements only. His son Ma Lin 马麟 [c.1180-1256] continued the style. Ma Yuan details… ➚ Ma Lin details… ➚

Xia Gui 夏圭 [d.1224]

With Ma Yuan founded a much admired school of landscape artists particularly in Japan and Korea. He has a more abstract style than Ma Yuan. Artist details… ➚

Mu Xi 牧溪 [c.1210-1269] (or Muqi or Mu-ch’i)

A much respected painter of the ‘Chan Buddhist’ school. He is famous for both landscapes and nature subjects for example ‘Six persimmons’ and ‘Mother monkey and baby’. More appreciated in Japan than in China. He makes expressive use of the brush in sparse composition with muted grays to give distance and mistiness. Artist details… ➚

Qian Xuan 钱选 [1235-1305] (or Ch’ien Hsüan)

Best known for painting animals and birds mostly in the Tang style with accurate and delicate brushwork. He remained in the south and did not go to the Yuan imperial court after the Mongol conquest. Artist details… ➚

Gao Kegong [1248-1310] (or Kao K'o-kung)

An artist but also President of the Board of Justice of the Yuan dynasty. An influential landscape painter who followed the style of early Song masters. Artist details… ➚

Zhao Mengfu 赵孟俯 [1254-1322]

A painter from the Yuan dynasty, he rejected the atmospheric Song landscape style and chose simple flat perspectives. Artist details… ➚

Huang Gongwang 黄公望 [1269-1354]

One of the most influential painters of the late Yuan dynasty. His painting ‘Dwelling in the Fuchan mountains’ is one of the most famous Chinese paintings. A dry brush technique quickly establishes distant trees while hills are only sketchily drawn. The oldest of the four great painters of the Yuan (Mongol) period. Artist details… ➚

Wu Zhen 吴镇 [1280-1354]

A famous painter from the late Yuan dynasty. His landscapes use graded washes with minimal details. “Fishermen” is one of his best known pictures (hand scroll). One of the four great painters of the Yuan (Mongol) period. Artist details… ➚

Ni Zan 倪瓒 [1301-1374]

Chiefly a landscape painter. His landscapes are noted for bare open spaces. He typically uses wet washes on which darker dry brushwork is added for trees and rocks. Paintings are light in tone, lacking the deep tonal contrasts of some other painters. One of the four great painters of the Yuan (Mongol) period. Artist details… ➚

Wang Meng 王蒙 [1308-1385]

A landscape painter who worked on paper, a nephew of Zhao Mengfu. Details are indicated by careful but rapid brushstrokes. Some paintings are a mass of intricate rock and foliage patterns. The youngest of the four great painters of the Yuan (Mongol) period. Artist details… ➚

Dai Jin 戴进[1388-1462] (or Tai Chin)

A landscape painter who founded the ‘Zhe school’ 浙派 based around Hangzhou. His paintings are of dramatic mountain backgrounds with sparse foreground figures and rocks. He served the Imperial court briefly at Beijing but wanted more freedom so he went home to Hangzhou where his work was unappreciated and he died in poverty. Artist details… ➚

Shen Zhou 沈周 [1427-1509]

Came from a rich family and founded the influential Wu school of painting at Suzhou. He brought about the revival of traditional landscape by scholar-officials. Artist details… ➚

Bian Jingzhao 边景昭 [early 15th century] (or Bian Wenjin or Bien Wen-chin)

A Ming dynasty artist who specialized in accurate portrayal of birds. Artist details… ➚

Wu Wei 吴伟 [c. 1459-1508]

A Ming dynasty landscape painter. He became a court painter to three Emperors and followed Dai Jin in style. His scenes with figures are quickly sketched while his landscapes are more meticulous. Artist details… ➚

Wen Zhengming 文征明 [1470-1559] (or Wen Cheng-ming)

A leading artist of the ‘Wu School’ 吴门画派 founded by Shen Zhou centered around Suzhou who rejected the move to the new Imperial capital at Beijing and continued to draw subjects from southern China. Artist details… ➚

Zhou Chen 周臣 [1460-1535]

One of the individuals who created a notable unique style in the early 16th century. His landscapes are fusions of the techniques of earlier masters particularly Li Tang. Artist details… ➚

Tang Yin 唐寅 [1470-1524]

A pupil of Zhou Chen who became a popular artist and considered one of the four master painters of Ming dynasty. He used graded washes to give depth to landscapes but did not really surpass Li Tang and other early masters. Artist details… ➚

Lu Zhi 陆治 [c. 1496-1576]

A prominent member of the Wu school of painters at Suzhou. His landscapes are light and peaceful. Somewhat related to the style of Ni Zan. Artist details… ➚

Xu Wei 徐渭 [1521-1593]

Xu was an eccentric but genius painter of the late Ming dynasty. Some consider him the founder of modern Chinese painting. His bouts of mental illness made life tough and he ended up alone and penniless even though he was once nominated for the top imperial position. His subjects are mainly flowers painted in a vigorous, free and expressive style. Artist details… ➚

Dong Qichang 董其昌 [1555-1636]

Dong was an influential writer and analyst of painting history and styles. His domineering attitude and categorization caused many errors to become fixed in art history. His painting style uses graded washes in a classical style which rarely include people. Artist details… ➚

Hu Zhengyan 胡正言 [c.1584-1674]

Hu is famous for bird and flower painting. His Ten Bamboo Studio produced many albums of paintings where originals were reproduced in graded color for the first time in particular 十竹斋书画谱 Shí zhú zhāi shū huà pǔ ‘Ten Bamboo Studio Manual of Painting and Calligraphy’ published in 1633. It remained a classic guide for 200 years. Artist details ➚

Hong Ren 弘仁 [1610-1663]

A Buddhist monk who chose a more individual and sparser style than traditional landscapes. Artist details… ➚

Kun Can 髡残 [1612- c. 1674]

Kun is famous for densely painted landscapes in a style similar to Dong Qichang. He included bright colors in the distance as an innovation. Artist details… ➚

Gong Xian 龚贤[c. 1618-1689]

An individualist painter of the early Qing. A leader of the Nanjing school who painted with many small marks and subtle gradations. Artist details… ➚

Bada Shanren 八大山人 [c.1626-1705] (or Zhu Da 朱耷)

A painter with a very expressive style of the early Qing. He seems to have suffered from bipolar disease and from middle age refused to speak to anyone. A great innovator in use of brushstrokes. Artist details… ➚

Wang Hui 王翚 [1632-1717]

The most famous of the ‘Four Wangs’ who continued the traditional style into the Qing dynasty. He learned by accurate copying of the great masters of the past. Artist details… ➚

Shi Tao 石涛 [1642-1707] (or Daoji (Tao-chi) or Yuan Ji or Kugua Heshang)

A rare example of a Qing dynasty who escaped the mainstream and has a recognizable individual style. As a distant relative of the Ming ruling family he sought refuge as a Buddhist and then finally a Daoist monk. He believed in a strong single brushstroke to act as the backbone for his paintings. He used subtle blues and browns to add to feeling of recession. Artist details… ➚

Gao Qipei 高其佩 [1660-1734]

Another example of an individualistic painter who went his own way. He took to painting with fingers and also with one long fingernail. Artist details… ➚

Jin Nong 金农 [1687-c. 1763]

One of the most famous of the ‘Eight Eccentrics of Yangzhou’ 扬州八怪 an influential group in the mid Qing dynasty centred on Yangzhou, Jiangsu. He used expressive brushwork with some pastel colors. Artist details… ➚

Luo Ping 罗聘 [1733-1799]

Considered a student of Jin Nong but developed his own personal style that became very popular and the last of the Yangzhou line of painters. Artist details… ➚

Zhao Zhiqian 赵之谦 [1829-1884]

Best known as a painter of flowers in the traditional style. Artist details… ➚

Ren Yi 任頤 or Ren Bonian [1840-1896]

A member of the reformist Shanghai school of painters working on a fusion of Chinese and western styles. He makes bold use of color and brushstrokes. Artist details… ➚

Qi Baishi 齐白石 [1864-1957]

One of the most famous and popular painters of this period. Some paintings have sold for over $100 million. He had an expressive and individual style particularly of flowers and animals. Artist details… ➚

Gao Jianfu 高剑父 [1879-1951]

Incorporated some elements of western art into paintings and took on some western subjects such as everyday life. He was based in the Guangzhou area. Artist details… ➚

Xu Beihong 徐悲鴻 [1895-1953]

A very famous modern artist noted for paintings of horses and birds in a free, energetic style. After the formation of the PRC in 1949 he became president of the Central Academy of Fine Arts and chairman of the China Artists Association. He adopted western perspective in many of his works. Artist details… ➚