The Silk Road : 丝绸之路

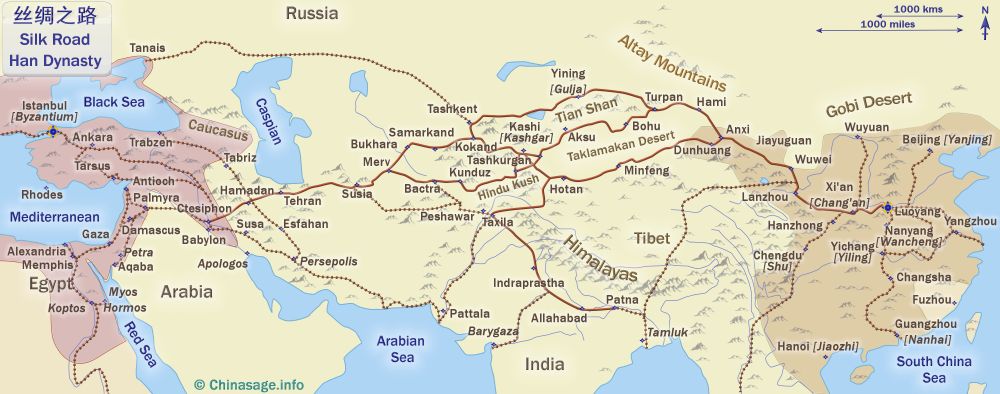

Europe and Asia at the time of the Roman and Han dynasties

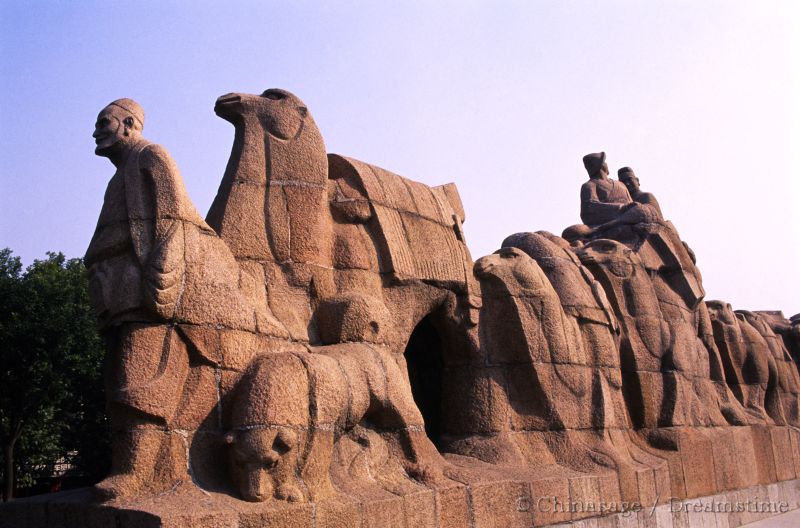

The Silk Road or Silk Route evokes a romantic vision of China; the imagination immediately conjures up camels carrying rare and exotic treasures thousands of miles through the desert landscapes of Central Asia.

The road was of great importance in the Han (200BCE); Tang and Yuan dynasties. Trade did begin at a much earlier date but on a much smaller scale as Chinese silk has been found in Afghanistan from 1500BCE. The Silk Route fell into decline during the Song and Ming dynasties when trade by sea from southern ports became safer and more profitable than the overland route. In fact there is not just 'one' road, instead it should be thought of as a network of roads as it has several branches, starting in both India and the Middle East and ending at the Chinese capital (for a long while this was at Luoyang, Henan province). There was also an overland route through Tibet to Bangladesh, from Chengdu to Hanoi and over the mountains of Yunnan into Burma. The name ‘Silk Road’ can only be traced back as far as the 19th century to the German geographer Baron von Richthofen ➚, it has never been known by this name in China. The trade along the route was much more significant to the Indians and Europeans than to the Chinese, as it carried only a small fraction of Chinese trade. The most exotic and expensive goods, silk, that could only be brought from China is reflected in the road's name.

The map above shows the Silk Road at about 100CE, when the Roman Empire extended into Asia Minor and the Han Empire had conquered much of modern China (except for Fujian). At the beginning of the Han dynasty explorer Zhang Qian ➚ spent 13 years on an eventful trek to the west where he married into the warlike Xiongnu tribe ➚ (who had held back Chinese expansion to the north-west). Zhang eventually brought back tantalizing news of advanced civilizations beyond China's borders. His journey into Parthia and India encountered traces of the Greek Empire that had been founded by Alexander the Great 356-323BCE ➚. Emperor Wudi's curiosity was piqued and he wished to find out more, including the exploration of a southern route into India through Yunnan. This first contact proved that China was not alone in developing an urban-based civilization.

The Silk Route was first used to import horses into China, which were needed to improve the effectiveness of Han cavalry against the skilled horsemen of the northern frontier tribes. With the new horses General Ban Chao ➚ was able to subjugate the Mongols. Thereafter more tales and rumors of the great, far away Roman Empire reached China. They learned such things as the Romans drank from glasses rather than earthenware cups. The Han dynasty name for Rome was Da Qin 大秦 ‘Great Qin’ named after the western Qin kingdom itself, apparently called ‘great’ due to their taller stature. Trade along the Silk Road between the two great empires grew rapidly. The Romans developed such a veracious appetite for silk that Emperor Tiberius introduced a ban to stem the outflow of gold. At this time it was the Sogdians ➚ centered at Samarkand who were the main traders along the route.

Silk Road cities

Along the Silk Route are many ancient trading posts: Bakhara, Kashgar, Tashkent, Kunduz, Samarkand ➚, Turpan and Tehran. The fortunes of these great cities ebbed and flowed as different peoples came into ascendency and Central Asia remained an area in flux for many centuries. Most chroniclers emphasize the long route to the Mediterranean and yet it was the trade with India which was more important. It was from India that many would say the most precious cargo was imported: the Buddhist religion.

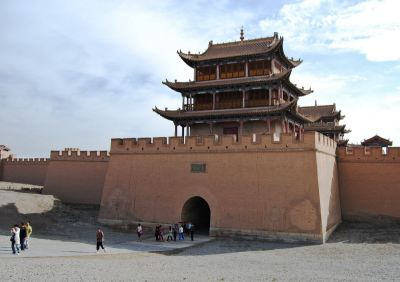

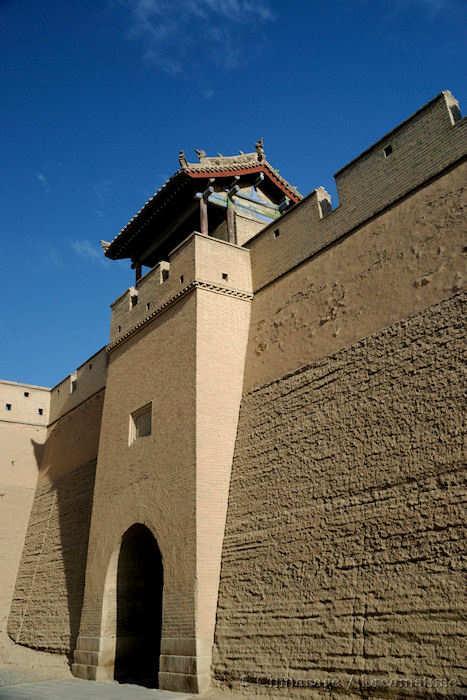

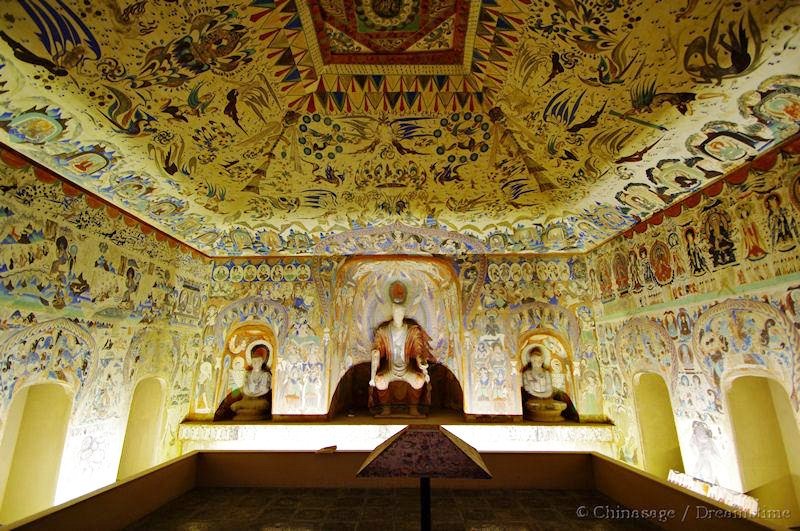

The grand western entrance into China was the Jiayuguan Gate, Gansu 嘉峪关 at the western end of the Great Wall of China. The Great Wall gave protection to travelers from attacks by tribes to the north on their passage deep into China through Lanzhou and on to the ancient capitals at Luoyang and Chang'an. When the Tibetan kingdom reached the height of its power in the Tang dynasty, Tibetans controlled the southern strands of the route. It was at Dunhuang, famous for its caves full of Buddhist paintings and scrolls, that the route divided - one route to the north of the inhospitable Taklamakan Desert to Central Asia and the other to the south with a branch to India.

Desert caravan

The traditional caravan that traveled the route was made up of a hundred camels roped together. They generally managed thirty miles a day, hoping to reach the next oasis in good time for sunset. Bells hung around the necks would enable any camels that broke free to be located and alerted caravans to each other's presence from afar. As well as their prodigious skill in storing water, camels were invaluable for finding new sources of underground water that they could sense and then paw at the ground to allow a temporary well to be dug. Knowledge of the exact route and weather conditions was passed down through generations of cameleers, to stray from the Silk Road was almost certain death. The journey was so long and arduous that they would normally make only one trip each year and so to make a decent living they had to transport very precious goods.

Perils of the Silk Road

There are only a few passes through the mountains into western China and even then climbing up to 9,843 feet [3,000 meters] was no mean achievement for the hardy traders and their beasts of burden. In the deserts of Taklamakan it was water that was the crucial commodity. Only limited amounts of water could be carried and these would last only a few days. An ancient civilization built the Karez (or Qanat ➚) water system to take the melt-water from the mountains and channel it underground down to the towns fringing the desert. The system at Turpan ➚ is the most impressive where melons and grapes can be grown using the hidden water supply. These irrigation systems were already in place two thousand years ago in the Han dynasty.

The Mongol conquest of China caused the whole of the route through Central Asia to come under Mongol control making travel safer and trade flourished. The route had always been subject to raids by bandits who would kill the porters and steal their precious cargo. The Silk Road into China at this time is described in the travels of Marco Polo. Trade was carried in stages by local tribesmen the Parthians, Bactrians and Sogdians of central Asia, who zealously maintained their role as middlemen. Only very few ever made the complete trek along the whole route. The lack of direct contact denied first hand knowledge in Europe of China and just as importantly China of Europe. However some Chinese inventions did make their way along the route including gunpowder, the abacus and silk. One of the 'new' goods that China did import were wooden chairs in pace of the traditional simple stools.

Exotic goods

As the name ‘Silk Road’ implies, silk was the most important goods transported as it is light, non-perishable and valuable. Silk was the ideal cargo for long distance journeys by land. At the time of Diocletian ➚ the price of silk is estimated to be $0.5 million per pound - more than its weight in gold. Apart from silk, China exported grain, lacquer-work, bronzes, decorated metalwork, diamonds, pearls and rhubarb (then believed to be the only reliable cure for constipation ➚). While in return imports of spices (from India and Central Asia) glass, coral (for decoration) woolen textiles, rhino horn, hides, ivory, fruit, amber, tortoiseshell, purple cloth and horses all came into China. Exotic birds and animals if they survived the long, grueling journey commanded a high price too. Diseases were a less welcome import and export, especially the Black Death ➚ that killed 100 million people also came along the silk road from Mongolia.

Decline of the Silk Road

The decline of the Silk Route started when northern China was conquered by the Jin and Xixia kingdoms during the early Song dynasty. The Southern Song dynasty had to rely on the sea to the south for trade because the overland silk road to the north was blocked off.

Although the Silk Road re-emerged as the main overland transport route during the Mongol dynasty when this fell in 1368 the overland route was no longer as safe. Central Asian kingdoms and their trading cities along the route had been devastated by the Mongol conquests. Northern barbarian tribes resumed their threat to the northern Chinese Silk route and more significant of all, advances in maritime technology allowed for safe and more profitable transport by sea as maps and compasses made the long distance sailing trips more practical. Even in Roman times there had been small scale but significant maritime trade via Sri Lanka and Arabia. By the start of the Ming dynasty the sea routes had become well established. This was another reason why the center of Chinese civilization moved south from the Yellow to the Yangzi River valley.

Silk Road re-discovered

After many of the silk road cities had been abandoned and buried in sand for centuries it was the turn of explorer-adventurers in the late 19th century to enter a race to discover them. There was great interest in Europe and America about the distant, exotic history of central Asia. Museums paid handsome rewards for ‘rediscovered’ (effectively stolen) treasures as they attracted many visitors. The explorers included Aurel Stein ➚ (UK); Paul Pelliot ➚ (France); Sven Hedin ➚ (Sweden); Albert von le Coq ➚ (Germany); Count Otani Kozui ➚ (Japan) and Langdon Warner ➚ (US). Some of the most prized relics were found at Dunhuang, Gansu.

Belt and Road initiative

In the last decade the Chinese government has begun an ambitious program to bring economic development along the line of the original Silk Route (as well as sea routes), not just in China but to Central Asian states as well. It is called the Belt and Road Initiative ➚ and was launched in 2015. Just like the ancient Silk Road the new over-land route will offer cost-effective transportation from China all the way into the heart of Europe.