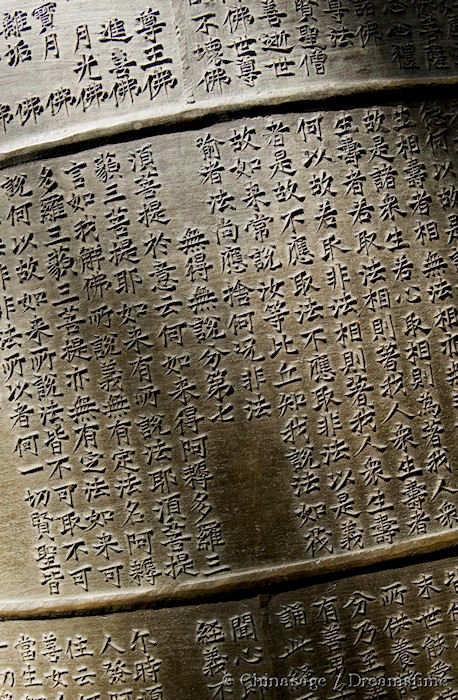

Traditional and Simplified Chinese characters

Chinese is a far older language than English and over the centuries has gradually gathered more and more characters (something like a total count of 200,000). Whenever a new concept arrived a new different character had to be devised for it and inevitably they have all become rather complex to keep them distinct. So there comes a time when it all would benefit from rationalization: simplifying complex characters and retiring archaic ones from everyday use.

Have you ever considered how much simpler it would be if English was reformed so it bore more relation to pronunciation? Children would learn it much more quickly and spelling mistakes would be a thing of the past! To see how arbitrary English spelling you only need to look at: bough (bow); cough (coff); dough (doe) and enough (enuff). Such a reform will, of course, never happen because you would have to reprint every single book and provide a very long period of transition when both systems are in use - people need to be able to read both forms but write only in the new one.

Chinese is in part symbolic as well as phonetic - there are Chinese languages that use the same written form but pronouncing it differently (e.g. Wu, Yue and Min languages). So many characters are not so tied to pronunciation as they are in English and so the job is easier.

Modern Revision

Mao Zedong declared ‘The Written language must be reformed; it must move with the same way as other written languages in the world’. A committee for the ‘Reform of the Chinese Written Language’ was created on October 10th 1949. This is another area where Mao can be compared to Qin Emperor Shihuangdi who brought in an overhaul of the script over 2,000 years ago replacing the many different written scripts with that of the Qin kingdom.

The revision of the Chinese language must be regarded as one of the most ambitious and successful of the reforms brought in by the People’s Republic. Long before 1949 there were reformers such as Lu Xun who had called for such an overhaul. Complex character forms are hard to recognize, remember and of course slow and hard to write. The cumbersome nature of old forms was a great obstacle to learning and was one reason why classic literature had remained the preserve of the educated élite. In 1949 adult literacy was only 20%. Only in the early days of the PRC could such a momentous change have been made, it would be impossible now. Occasionally such a great overhaul of the written language is needed - it cannot be done piecemeal.

The first set of simplified characters was announced in 1956 with further additions in 1964. 400 characters were discarded and 798 given new simplified forms. An additional tranche of changes was proposed in 1977 but they were rejected as a simplification too far and are not used. This rejected proposal made all characters strictly phonetic - an element in each character gave the pronunciation. Calligraphers, writers and historians continue to lament the loss of some of the old forms that are rich in heritage. A move to replace characters with pinyin has faded now that computers and smartphones have made the entry of characters far easier. Another obstacle to the universal adoption of the alphabetic pinyin is that there are far too many characters that are written identically in pinyin - it is rather ambiguous. The use of computers for writing characters has made the case for simplifying the language for ease of writing much less important than previously as people no longer need to write them by hand - stroke by stroke.

Traditional 繁体字 and Simplified 简体字

The new simplified form of written Chinese jiǎn tǐ zì was not adopted outside the Peoples Republic and so the traditional form fán tǐ zì is still used in Taiwan, Malaysia and Hong Kong but not Singapore. There is a gradual move to the simplified form in Hong Kong but there is still resistance elsewhere, particularly in southern China. Anyone who wants to read old books and documents has to memorize both forms of the characters. Some experts promote the mantra ‘think traditional, write simplified’. Unfortunately some web sites still use only the traditional forms, and even worse some use a mixture of simplified and traditional - due no doubt to copying and pasting of text. Many times I have failed to find a character in my modern dictionary only to discover it is in the traditional form. The Japanese have introduced their own set of entirely independent simplifications of the original Kanji script that they inherited from China in the Tang dynasty.

The Simplifications

The Chinese committee used a variety of different approaches when creating the simplified form. The main target was to reduce the number of strokes needed to write each character.

Existing alternative forms

There had been some piecemeal simplifications over the centuries, where characters had both an accepted complex and a simple form for example none 無 wú already had the recognized form as 无. Throughout the Imperial era there was both a literary and an everyday script; scholars were not supposed to use the simplified forms which were in use by ordinary people. The everyday script versions of characters are often simpler; for example cloud 雲 gained the rain radical 雨 yǔ on top in the official script, while previously it was just 云 yún, so the older version could simply be re-adopted. Another dramatic example of simplification is dust 塵 chén that adopted an older form 尘 which is a pleasing combination of just ‘small’ 小and ‘soil’ 土.

Following this ancient precedent many common characters were simplified by just omitting the radical part. So electricity 電 diàn lost the rain radical (from its association with thunderstorms) to become 电. The common character open; begin 開 kāi lost its door radical to become 开. A dramatic simplification of 廣 to 广 guǎng for vast or wide leaves just the radical part remaining. In this case an empty space is an appropriate representation.

Flowing script

Calligraphers use a variety of scripts to write Chinese, the much admired flowing grass script uses far fewer strokes to write the same character; so one approach to simplification is to adopt the character used in other scripts. An example of this is east written as 东 dōng in the grass script rather than the full form 東. Another example is book 书 shū which is much simpler than 書. There is also the rather appropriate study 學 xué (16 strokes) which now uses the simpler 学 form (8 strokes).

Simpler Phonetic

Many Chinese characters (about 80%) have a phonetic hint indicated by another character element that has the same sound. As the phonetic part does not contribute to the meaning it is sensible to choose the simplest available phonetic element. So park or garden 園 yuán became 园 by replacing the phonetic element 袁 yuán with 元 yuán. Also calendar 曆 lì became 历 by using the simpler phonetic 力 and neighbor 鄰 lín (15 strokes) becomes 邻 (7 strokes).

Streamlining

The easiest way to simplify is to miss out one or two strokes from the old form but retain the recognizable layout of the original. Examples in this category include the character for bird 鸟 niǎo which retains the impression of a bird with fewer strokes than 鳥 and arrive 来 lái for 來. Similarly speak 說 shuō has become 说 by replacing the traditional ‘complex’ speech radical 訁 (seven strokes) with 讠 (two strokes). The pictograph form for tortoise 龜guī lost its legs to become 龟 with only a head, shell and tail. Quite a dramatic and pleasing example is fly 飛 fēi which became a single wing 飞 the empty space giving the idea of ‘air’.

New forms

Sometimes the character has been replaced with a new, simpler symbol which uses fewer strokes; this is the only situation where new forms have been invented. So wind 風fēng which has the character for an insect inside has become simply 风. Also correct 對 became 对 duì with a simplified symbol. These changes met the fiercest opposition as the change was arbitrary. In the case of wind the use of insect was considered appropriate because insects were thought to be brought in by the winds.

Merging

For some rather obscure characters not in widespread use, several old characters with the same pronunciation have been merged into one new character. For example you 臺; desk 檯 and typhoon 颱 have all become 台tái.

Recycling

With such a venerable written language there have been many characters that have fallen out of use. So some of these unused, simple forms could now be re-used to replace some common ones even though the meanings have no relation to each other. The complex form for how many 幾 jǐ was changed to 几jǐ which originally was used for a small table. Similarly strife 斗 dòu replaced 鬥dòu which was an old character that was a homophone for an ancient measure of grain.

Conclusion

As both forms can still be found here and there anyone studying the written language still needs familiarity with both forms. Understanding the old form often gives an insight into Chinese culture and history so it is certainly a rewarding exercise.

Common simplified characters

Here is a table of some common Chinese characters that have been simplified. The first column is the traditional form, the second the simplified form and then the pinyin and English.