Chinese Calligraphy 书法 shū fǎ

Calligraphy in the west is mostly associated with recreating the illustrated medieval script. It has always meant much more in China; a career in calligraphy is a well respected profession. Up until the recent rise of computers there was no real alternative to hand written script, as typewriters could not cope with the large number of Chinese characters. There is a close relationship between calligraphy and painting, a piece of calligraphy is considered a work of art in itself and valued above that of paintings. The techniques of calligraphy are used in painting. Many great paintings are complemented with a poem inscribed on them in fine calligraphy quite often one composed by the artist himself. With the complex forms of characters there is much more scope for expressing individuality into the writing compared to English and other languages with a small alphabet. The calligrapher signs the work by adding the imprint of a chop ➚ with red waxy paste or ink (originally colored with cinnabar). A fine painting may bear several poems by different writers at different times, and will often bear the red seal marks of the succession of proud owners as well as the calligrapher. As it was necessary to be able to write well and clearly for the Imperial examinations, all aspiring scholars had to spend many hours practicing calligraphy.

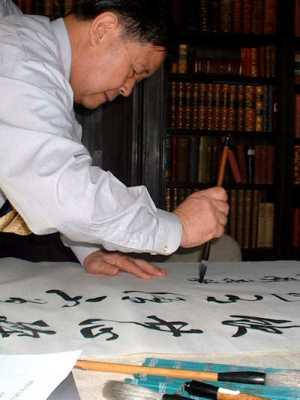

The use of a brush rather than a rigid stylus dates back to the Qin dynasty when the script was standardized, using a brush rather than a pen had a fundamental influence on Chinese culture. By the time of the Ming dynasty more importance was put on the artistry of the calligrapher than the text that was represented.

Calligraphy styles

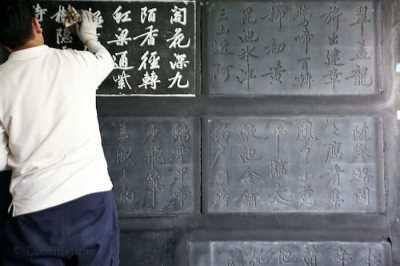

Different styles of stroke have given poetic names such as ‘playful butterfly’; ‘dewdrop’; ‘leaping dragon’ and ‘milling waves’. Types of calligraphic stroke have different qualities they are categorized as bone (骨 gǔ), flesh (肉 ròu), muscle (or tendon) (筋 jīn) and blood (血 xuè). Blood is the wetness or dryness of the stroke; muscle the strength of the stroke; bone the structural layout and flesh the weight (thickness) of the stroke. A person's personality is widely regarded to be evident from their calligraphy. Although calligraphy has only eight basic strokes there are many options in terms of weight, strength and layout of each character. The work of master calligraphers is often copied as a tribute to the original artist. The finest examples of calligraphy are inscribed on stone (called steles) so that students can take away their own rubbing of the stone using wax over paper. For example there are an appropriately large number of steles at Confucius' birthplace at Qufu. The Classics of Chinese literature were inscribed in 175CE near the capital Luoyang for students to copy; 200,000 characters were engraved on fifty huge stones, a process that took eight years to complete.

Wang Xizhi 王羲之 [303 - 361] or Wang Hsi-chih WG

Wang Xizhi is considered the sage of calligraphy. He developed the flowing grass script in contrast to the solid square official script. His calligraphy has been described as “light as a floating cloud; vigorous as a startled dragon”. He lived at the time of Period of Disunity when the Eastern Jin dynasty tried and failed to keep hold of power in northern China. This was the time that the production of paper had become widespread and of good quality. Wang Xizhi was taught by Lady Wei (卫铄 Wèi shuò) and he kept a flock of geese which may have influenced his style. The graceful curve of their necks greatly appealed to him. He also studied how geese moved their necks and this inspired the way he moved his arm to make smooth and graceful strokes. Wang gave up a career as an official to study only calligraphy, learning from all the acknowledged masters of the time. It is said that he practiced so long and ardently that he turned a pond black with the ink he discarded.

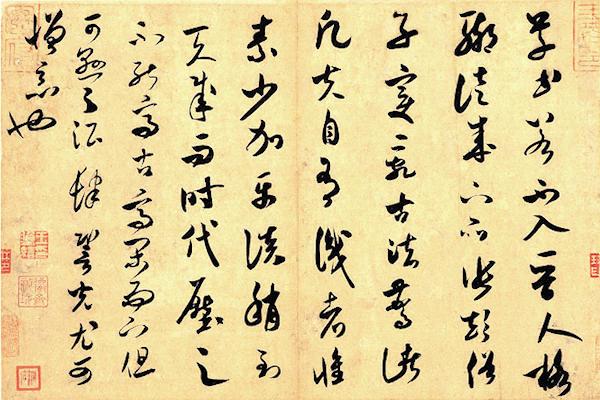

His work has been copied and re-copied down the centuries as it was as close to perfection that could be achieved. His style is called ‘xing shu’ 行書 or ‘moving writing’ which has a flowing style. Copies were usually made by taking rubbings of the calligraphy engraved in stone. Although his son Wang Xianzhi 王献之 was as great (if not greater) calligrapher by the time of the Tang dynasty Wang Xixhi reputation was fixed in history. His work is still very highly prized with prices in the tens of millions of dollars for copies with sound provenance.

His most famous work ‘Preface to poems composed at the Orchid Pavilion’ 兰亭集序 Lán tíng jí xù is about a party for 42 guests at Lan Ting (兰亭) near Shaoxing, Zhejiang. Each had a drinking cup that was set upon the waters, when the cup stopped moving its owner had to compose a poem. There is a similar story attached to the Xishang Pavilion ➚ at the Forbidden City where a water channel was fashioned for cups to float along. Another famous work is ‘Timely Clearing After Snowfall’ ➚ 快雪晴帖 kuài xuě qíng tiě)

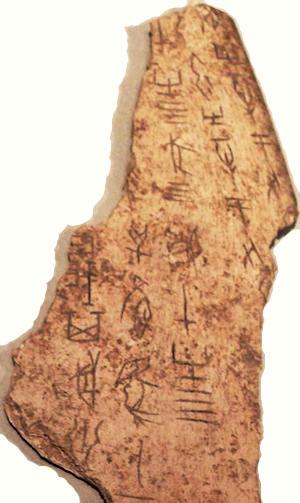

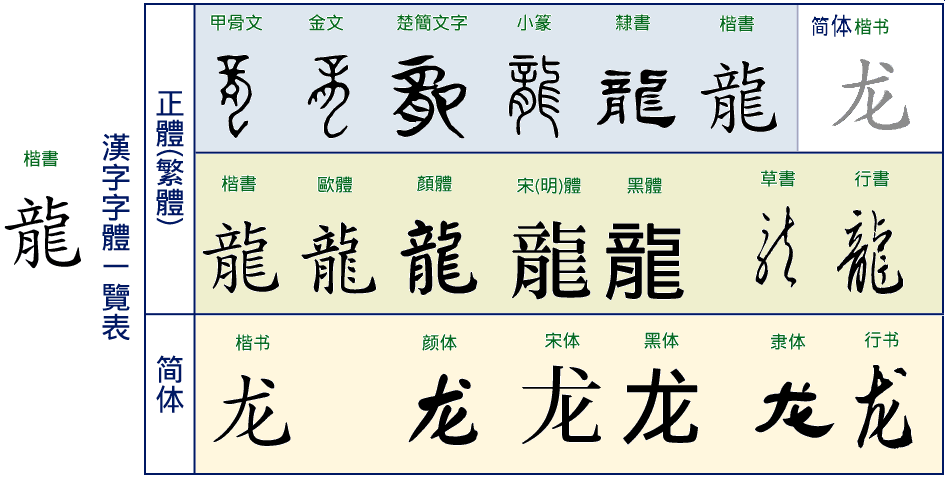

There are over a dozen recognized styles of calligraphy that have been used in the last few thousand years. The Dà zhuàn 大篆 (large seal) is the ancient form of characters attributed to the Yellow Emperor 4,000 years ago. These were inscribed on bronze and bone and did not use a brush. However an earlier form of the Shang dynasty 'Shell and Bone' 甲骨 Jiǎ gǔ was used for writing on oracle bones and other records. The Qin Emperor (210BCE) introduced the xiǎo zhuàn 小篆 (small seal) as the standard for the empire. The reform was brought in by his chief minister Li si ➚. The characters on seals (or chops) use the zhuàn shū 篆书 ➚ script to this day. The clerical script Lì shū 隶书 evolved from the earlier rectilinear forms of script to become the official script of record in the Han dynasty. At this time writing was on thin strips of bamboo which limited flexibility, when paper became widely used during the Han there was much more opportunity for flexibility in brushwork. Li shu is the most complex script to master and the first to develop after the brush was used for writing. This style became standardized as it was the required form for the written examinations. From this script the Japanese derived their kanji ➚ characters.

For rapid writing a more flowing script is needed, this was achieved with the cǎo shū 隶书 (grass script) which introduced many drastic simplifications to allow characters to be drawn in a single, flowing stroke; this makes them more rounded and harder to decipher. It has been described as 'Dancing on paper' and is more to do with art than writing. For writing rather than reading the usual script used is the xíng shū 行书 semi-cursive script, literally ‘walking script’ that is sufficiently close to the rectilinear form to be understood and yet quick to write. The xing shu is the normal ‘hand-written’ form of Chinese. The regular, official script used today is kǎi shū 楷书 which began to be used in the Han dynasty was finally frozen in form in the Tang dynasty. The characters are written in a standard space and are designed to be easy to read. This is the script that children learn to read so it is also known as 真书 zhēn shū ‘regular script’.

Flowing scripts

Flowing scripts are associated with the Great Sage of Calligraphy Wang xizhi although he is considered master of all styles. For speed of writing the strokes are drawn as one joined up motion of the brush but the standard square shape is maintained. The most eccentric and flowing script is called ‘Mad grass’ 狂草 kuáng cǎo where characters can take on large and exaggerated forms.

The last major change to the script was in the 1960s when characters were simplified to make reading easier and writing quicker. The modern, simplified form is called 简体字 jiǎn tǐ zì ‘Simplified form of letters’

Emperor Huizong ➚ of the Song dynasty was a gifted calligrapher and painter, his ‘thin gold’ calligraphy set the standard for fine Imperial script. Calligraphy is still much appreciated, many of Mao Zedong’s works included hand-written titles and phrases. The masthead (title) of the party newspaper ‘The People's Daily ➚’ 人民日报 used Mao's own handwriting.

The main primer for schoolchildren to learn their characters was the 1,000 character classic that has 1,000 unique characters. Since it was written 1,5000 years ago it has been written in a wide variety of scripts.

Four Treasures

The Four Treasures of the Scholar 文房四宝 wén fáng sì bǎo are: brushes, ink stick, ink stone, and paper (笔墨纸砚 bǐ mò zhǐ yàn). To these are added the seal (or chop), cinnabar paste and a brush-stand in the traditional form of a mountain.

The ink is usually provided in solid form as a stick, this is ground up with water to provide ink when needed. The stick is made from soot from the burning of conifer wood and bound with glue (originally from rice starch). Many ink sticks are decorated with traditional scenes.

The ink stone ➚ has a smooth area for grinding the ink stick with water. It is typically made from slate or similar fine grained stone. Perhaps the most prestigious ink-stones are the 端砚 duān yàn from Duan, Guangdong. Anhui province is also famous as a source of good ink-stones.

The brush is traditionally of fur which may come from goat, rabbit, camel, mouse, badger, pine marten or other animals. It is a thick brush that can take up a lot of ink for thick strokes and yet come to a very sharp point to make fine strokes. The shaft of the brush is normally made of bamboo. Each stroke has to be made in a single movement; it does not allow for hesitation midway through or for later correction.

Paper is usually used for calligraphic work but silk and linen is also used. The paper, such as rice paper, can be as thin and absorbent as 'tissue' paper making writing more of a challenge. Bamboo paper is often used for practice. It comes in 'sized' and 'unsized' forms, 'sizing' adds a layer to the paper surface to make it less absorbent. For fine, detailed work a fully sized paper is best, while for practise semi-sized paperr isnormally used - the ink spreads out a little but not too much.